Earlier this week, a new player joined my group, and in the manner of our people she rolled up a new character: 3d6, in order, just like it's meant to be. Her stats were as follows: Str 14, Dex 15, Con 14, Int 4, Wis 18, Cha 8.

She looked up from her character sheet and asked: 'How am I meant to play this?'

The tricky bit was the Int and Wis combination, of course. High Int and high Wis just means that you're really clever; low Int and low Wis just means that you're really stupid. High Int and low Wis is pretty easy; everyone knows people who are academically gifted but have no common sense whatsoever. Low-ish Int and high Wis isn't too bad: it's easy to imagine someone being really wise despite not having any kind of 'book learning' or aptitude for abstract reasoning. (For some reason, people usually seem to play them as folksy rural types.) But Wisdom 18 and Intelligence 4? How can you be both super-wise and super-stupid?

In the event, she decided to play her PC as a kind of weird, witchy, primal character: totally illiterate, largely innumerate, shockingly ignorant... and yet with a kind of instant, empathic, intuitive understanding of the world, which allowed her to instantly understand situations in bursts of wordless insight. (Rather fittingly, she promptly bashed some guy's brains out with a skillet and became a priestess of Tsathogga.) She didn't really come across as a stupid person in play, though; rather, she came across as an extremely intelligent person whose mind just didn't quite work in the same way as other people's. As a character it was great, but I'm not sure how well it reflected what was written on her character sheet.

Since the session, I've given it a bit more thought, and I reckon that you could simultaneously portray both very high wisdom and very low intelligence either by playing as a kind of 'holy fool', or as a near-feral character who runs almost entirely off instinct. Those both seem kinda narrow, though. 'Wolf girl or idiot mystic' is a pretty slim range of choices for a character you've just rolled up.

Anyone else have any ideas? How have you played very high Wis, very low Int characters in your campaigns?

Romantic clockpunk fantasy gaming in a vaguely Central Asian setting. May feature killer robots.

Pages

▼

Thursday, 29 September 2016

Monday, 26 September 2016

B/X Class: The Extras

I was reading through issue three of Brave the Labyrinth (get it! It's free!) when I came across the Grimp character class. The idea behind the class is that, rather than playing one character, you play a whole group of tiny imps (grimp, geddit?), all standing on one another's shoulders, using limited telepathy and acrobatic skills to coordinate their actions as though they were one creature. The number of imps in your 'body' is equal to your hit points: so if you have ten HP, you're a pile of ten little imps, and so on.

Now, I really liked this idea, but it made me think: could the idea of one player playing a group of characters, all of whom collectively act as one character, be taken further? And then my eye fell upon my Pirates of the Carribean DVDs, and I came up with this:

The essence of playing as The Extras is that you aren't playing as a specific group with clearly-defined numbers and capabilities (e.g. 'the six archers Alice hired in the city'): use the regular henchmen and followers rules for those. Instead, you're playing as that bunch of guys who are milling around in the background in every scene. Every time you get in a dangerous situation, one or more of you probably dies just in order to show that things are serious; but, mysteriously, these deaths never seem to affect your overall numbers. If, for any reason, it ever becomes necessary to determine exactly how many of you there at a given moment, then roll 1d12+6; but the number rolled has no effect on how many of you there are in the next scene, or indeed in the next combat round.

Die All, Die Merrily: If The Extras are ever reduced to 0 HP, describe them all dying in some suitably tragi-comic fashion. The only survivors of this massacre will be the Named Characters. The person playing The Extras can immediately continue play as Sarge, who can be assumed to be a Fighter of one level lower than The Extras; the other Named Characters will be fighters of half the level of The Extras, rounded down, who will instantly become Sarge's henchmen (or someone else's, if this would take Sarge above their limit.) Each of these characters emerges from the general massacre with only (1d6x10)% of their maximum HP.

Now, I really liked this idea, but it made me think: could the idea of one player playing a group of characters, all of whom collectively act as one character, be taken further? And then my eye fell upon my Pirates of the Carribean DVDs, and I came up with this:

B/X Class: The Extras

You aren't one person at all: instead, you are playing an indeterminate mob of nameless minor characters who follow the other PCs around. You might be a pirate crew, a band of Merry Men, a bunch of faceless stormtroopers, or anything else, but two facts remain constant: there are a lot of you (although exactly how many seems to vary from scene to scene) and, despite your numbers, collectively you only manage to achieve about as much as each of the main characters does individually. At best.

| You're not playing Barbosa. You're playing the other guys. |

The essence of playing as The Extras is that you aren't playing as a specific group with clearly-defined numbers and capabilities (e.g. 'the six archers Alice hired in the city'): use the regular henchmen and followers rules for those. Instead, you're playing as that bunch of guys who are milling around in the background in every scene. Every time you get in a dangerous situation, one or more of you probably dies just in order to show that things are serious; but, mysteriously, these deaths never seem to affect your overall numbers. If, for any reason, it ever becomes necessary to determine exactly how many of you there at a given moment, then roll 1d12+6; but the number rolled has no effect on how many of you there are in the next scene, or indeed in the next combat round.

Game rules for playing The Extras are as follows:

Hit Dice: 1d12. The Extras aren't individually very tough, but there are a lot of them.

To-hit, Hit Dice, Weapons and Armour, Saves: As per Fighter.

Experience Per Level: As per Magic-User.

Safety In Numbers: Apart from named characters (see below), The Extras always go around in a single big mob. If you use a battle grid or similar, assume that this mob of extras takes up an area 20' square whenever possible. (In a 5' wide tunnel, they'd form a single line 5' wide and 80' long.) They always move as a single mass, and can attack or be attacked by anything within 5' of the mob.

Inverse Ninja Rule: Even though there are so many of them, The Extras only get a single action per round: so a whole mob of Extras attacking a monster is resolved with a single attack roll, and so on. (The exception is Named Characters - see below.)

Many Hands Make Light Work: Whenever they're performing some kind of unskilled labour - e.g. standing watches, digging ditches, carrying treasure, rowing oars, etc - The Extras can accomplish the work of ten men. Even though there are more of them than that. Probably. Most of the time.

|

| 'Who are you people? Why do you keep following me around?' |

Share the Pain: The Extras have a single HP total. Any healing or damage done to any of them affects them all. Weirdly, area-of-effect damage only damages them once rather than many times, almost as if they really were just a single creature...

Arm the Troops: For The Extras to gain mechanical benefits from new equipment, they must obtain at least ten copies of the equipment in question: so once they have ten swords they can make sword attacks, and so on. If they have less than ten, then some of them can be described as carrying the equipment in question, but they gain no mechanical benefit from it. (Oddly enough, this does not extend to consumables like rations and ammunition, which The Extras consume as though there was only one of them present.)

| Too bad these Extras only have five sets of legionnaire gear! No bonuses for them! |

Magic For the Masses: The Extras can collectively have any number of magic items 'equipped' at once, but they can only gain the mechanical benefit from each item once per scene. (The guy with the magic sword steps up to take a swing, or the guy with a magic shield steps up to block a blow, and then they just fade back into the mob.) If the item in question is assigned to a Named Character (see below), then its benefits also apply to any independent actions they may take.

Named Characters: At level 1, give one of the Extras a name and a personality, just as you would for a normal PC. This character (whom the other Extras will usually call 'Sarge') acts as the 'face' of the mob, and is the character who you will play during social interactions and similar roleplay-focussed scenes. (Naturally, the rest of the Extras never get any lines.)

Once per scene, you may have this character take an action independently of The Extras: so The Extras could attack an orc while Sarge ran off to warn the other PCs, or whatever. This is the only exception to the rule that The Extras must always act as a single unit, and it effectively gives you two actions for that round only. Next round, Sarge is assumed to have been absorbed back into the general group, and will spend the rest of the scene acting as part of the mob.

Each time you level up, you may create one more Named Character, by giving one of The Extras a name and a single distinguishing characteristic. (E.g. 'Private Wilkins, always drunk'.) Just like Sarge, each of these named characters may also take one independent action per scene, but only one named character may take such an action per round.

- Example: Kat's Cutthroats (level 3) have three named members: Kat herself (their Sarge), No-Ears Jake (their musician), and Silver Fork Sarah (who claims, and may actually believe, that she is secretly a princess). When they get into a fight with some goblins, the Cutthroats may act twice on up to three rounds of the ensuing combat: the Cutthroats take one collective action per round, in one round Kat can take an action, in one round Jake can take one, and in round Sarah can take one. Once all three Named Characters have taken one action each, the Cutthroats revert to their normal single collective action per round.

Die All, Die Merrily: If The Extras are ever reduced to 0 HP, describe them all dying in some suitably tragi-comic fashion. The only survivors of this massacre will be the Named Characters. The person playing The Extras can immediately continue play as Sarge, who can be assumed to be a Fighter of one level lower than The Extras; the other Named Characters will be fighters of half the level of The Extras, rounded down, who will instantly become Sarge's henchmen (or someone else's, if this would take Sarge above their limit.) Each of these characters emerges from the general massacre with only (1d6x10)% of their maximum HP.

- Example: Kat's Cutthroats (in the example above) are reduced to 0 HP by the goblins. The only survivors are Kat (who becomes a level 2 fighter, and a new PC), and Jake and Sarah (who become level 1 fighters, and Kat's henchmen).

If all the named characters survive the adventure and make it back to town, they may recruit a new band of faceless followers and regain their status as The Extras. If this happens, then the Named Characters merge happily back into the new mob. If, on the other hand, Sarge or any of the other Named Character goes on to die before a new band of Extras can be recruited, then the remaining ones decide sorrowfully that It Would Never Be The Same Without Them and remain as ordinary PCs and henchmen forever.

Saturday, 24 September 2016

Almost a review: Sinister Serpents

Derek Holland, author of Basilisk Goggles and Wishing Wells, evidently liked the review I wrote of it enough to send me his latest ebook, Sinister Serpents: New Forms of Dragonkind. It's 29 pages long - 24 pages of content plus five of front and back matter - and it contains Labyrinth Lord-compatible write-ups of 38 new types of dragons. As you'd expect, the statblocks are very minimal (and, frankly, you could usually have worked out most of the stats yourself based on the accompanying descriptions), so essentially you're paying $6 for thirty-eight two-to-four-paragraph dragon ideas. This makes me slightly wary of saying too much about the dragons themselves, as basically every time I mention one I'm giving away just under 3% of the book's content for nothing...

...so. Dragons. They live at the bottom of your dungeon, sleeping on a big pile of treasure and waiting for greedy and/or high-level PCs to sneak in and get eaten. As niches go, it's a pretty small one, and yet D&D and its derivatives has hundreds of different types of the damn things. Fire dragons. Ice dragons. Good dragons. Bad dragons. Shiny dragons. Psychic dragons. Zombie dragons. Toad dragons. That stupid lust dragon whose breath weapon makes everyone's clothes fall off. (I wish I was joking about that one.) You can easily use a dozen or more humanoid races over the course of a campaign; hell, you can easily use a dozen or more humanoid races over the course of a single dungeon. But how many dragons is any one game likely to need? In all my years of running fantasy RPGs I think I've only run five dragon encounters, and one of those was with an abstract metaphysical force which just happened to currently be dragon-shaped.

The traditional way in which writers have diversified D&D's stable of dragons is via combat role: stronger dragons, weaker dragons, dragons with weird special abilities, dragons which use obscure energy types as breath weapons, and so on. Sinister Serpents takes a different approach: it diversifies dragons via ecological role. Stat-wise, they're mostly pretty similar: they have good AC, a high number of hit dice, claw and bite attacks, and a breath weapon that fucks you up. But the roles they play in the world are diversified: there are dragons as natural disasters, dragons as ambush predators, dragons as symbiotic parasites, dragons as natural resources, dragons as industrial powerhouses, dragons as community protectors, dragons as factors in geological and ecological development, and so on. It's an original approach, and one that I think has more to recommend it than the traditional 'dragon that breathes [X] instead of fire' method. How useful it will be, on the other hand, is ultimately going to depend on how much of a role you want dragons to play in your campaign.

This comes back to a point I've made before: the bigger a monster is, the less useful it tends to be in actual play. A game needs many minions but few boss monsters, and the bigger a monster is, the more it tends to shut down play in the game-world around it. The nature of power is to limit action within its range of operation: that's what power is, the ability to decide that things will happen in this way rather than that way and actually have that take place. As the monster in the next room gets more dangerous, an ever-increasing number of ways in which your PCs might want to approach the situation get overwritten with 'no, it'd just stomp on us'. A certain amount of such constraint is essential to spark player creativity, but too much of it leaves players with very little room to manoeuvre.

The dragons in this book are still mostly basic D&D-style creatures with 8 HD or thereabouts, tough but still eminently killable, rather than the mega-monsters which dragons would go on to become in later editions of D&D. But they're still dragons: and they are, with a few exceptions, big and powerful enough to make a pretty big impact on the world around them. Their special abilities are mostly similarly flashy, powerful enough to exert a significant influence upon the local landscape or economy or ecology. They're a big deal. How many big deal dragons do you want in your game? How many do you need? How often do you want the answer to major questions about the way your campaign world works to be 'a dragon did it'?

If the answer is 'loads', or even 'quite a lot', then you'll probably enjoy this book, which is full of weird dragons who can affect their environments in all kinds of interesting ways. If it's 'not very often', then... well... you'll probably still enjoy it, because there are some nice ideas here. But you might struggle to make use of many of them in actual play!

...so. Dragons. They live at the bottom of your dungeon, sleeping on a big pile of treasure and waiting for greedy and/or high-level PCs to sneak in and get eaten. As niches go, it's a pretty small one, and yet D&D and its derivatives has hundreds of different types of the damn things. Fire dragons. Ice dragons. Good dragons. Bad dragons. Shiny dragons. Psychic dragons. Zombie dragons. Toad dragons. That stupid lust dragon whose breath weapon makes everyone's clothes fall off. (I wish I was joking about that one.) You can easily use a dozen or more humanoid races over the course of a campaign; hell, you can easily use a dozen or more humanoid races over the course of a single dungeon. But how many dragons is any one game likely to need? In all my years of running fantasy RPGs I think I've only run five dragon encounters, and one of those was with an abstract metaphysical force which just happened to currently be dragon-shaped.

The traditional way in which writers have diversified D&D's stable of dragons is via combat role: stronger dragons, weaker dragons, dragons with weird special abilities, dragons which use obscure energy types as breath weapons, and so on. Sinister Serpents takes a different approach: it diversifies dragons via ecological role. Stat-wise, they're mostly pretty similar: they have good AC, a high number of hit dice, claw and bite attacks, and a breath weapon that fucks you up. But the roles they play in the world are diversified: there are dragons as natural disasters, dragons as ambush predators, dragons as symbiotic parasites, dragons as natural resources, dragons as industrial powerhouses, dragons as community protectors, dragons as factors in geological and ecological development, and so on. It's an original approach, and one that I think has more to recommend it than the traditional 'dragon that breathes [X] instead of fire' method. How useful it will be, on the other hand, is ultimately going to depend on how much of a role you want dragons to play in your campaign.

This comes back to a point I've made before: the bigger a monster is, the less useful it tends to be in actual play. A game needs many minions but few boss monsters, and the bigger a monster is, the more it tends to shut down play in the game-world around it. The nature of power is to limit action within its range of operation: that's what power is, the ability to decide that things will happen in this way rather than that way and actually have that take place. As the monster in the next room gets more dangerous, an ever-increasing number of ways in which your PCs might want to approach the situation get overwritten with 'no, it'd just stomp on us'. A certain amount of such constraint is essential to spark player creativity, but too much of it leaves players with very little room to manoeuvre.

The dragons in this book are still mostly basic D&D-style creatures with 8 HD or thereabouts, tough but still eminently killable, rather than the mega-monsters which dragons would go on to become in later editions of D&D. But they're still dragons: and they are, with a few exceptions, big and powerful enough to make a pretty big impact on the world around them. Their special abilities are mostly similarly flashy, powerful enough to exert a significant influence upon the local landscape or economy or ecology. They're a big deal. How many big deal dragons do you want in your game? How many do you need? How often do you want the answer to major questions about the way your campaign world works to be 'a dragon did it'?

If the answer is 'loads', or even 'quite a lot', then you'll probably enjoy this book, which is full of weird dragons who can affect their environments in all kinds of interesting ways. If it's 'not very often', then... well... you'll probably still enjoy it, because there are some nice ideas here. But you might struggle to make use of many of them in actual play!

Friday, 23 September 2016

[Actual play, sort-of] Adventures with a two-year-old

My son is now almost two and a half, which means he's started engaging in imaginative play. Playing with him increasingly feels like running a game of D&D with the most anarchic players in the world.

Imagine if, when you said to your players, 'OK, you get in the wagon. What do you do now?', there was a roughly 50% chance of them replying: 'I crash it into the nearest wall!' It's kinda like that.

(I mean, he doesn't actually say that. He just grabs the vehicle and rams it into a wall while shouting: 'CRASH! Oh no! Help me, guys!' But the message is pretty clear.)

Here's an after-the-fact 'actual play' report of a fairly representative 20-minute slice of play. Its similarity with a lot of real RPGs I've played in over the years makes me wonder just how much of gaming is really about reconnecting with your inner two-year-old...

Imagine if, when you said to your players, 'OK, you get in the wagon. What do you do now?', there was a roughly 50% chance of them replying: 'I crash it into the nearest wall!' It's kinda like that.

(I mean, he doesn't actually say that. He just grabs the vehicle and rams it into a wall while shouting: 'CRASH! Oh no! Help me, guys!' But the message is pretty clear.)

Here's an after-the-fact 'actual play' report of a fairly representative 20-minute slice of play. Its similarity with a lot of real RPGs I've played in over the years makes me wonder just how much of gaming is really about reconnecting with your inner two-year-old...

|

| Our intrepid heroes: Lars (left) and Xuli (right). |

|

| Lars and Xuli are drowning in paper! 'OH NO! HELP ME, GUYS!' |

|

| Lars and Xuli are rescued by a friendly car. |

|

| They meet a lizard monster who lives in a castle on wheels. |

|

| Lars and Xuli steal the castle and crash it into a wall. |

|

| A dragon knocks the castle over and chases everyone away. 'Imma get you! OH NO! GRR!' |

|

| Xuli attacks the dragon with a giant drill. |

|

| Having defeated the dragon, Xuli flies off in an aeroplane. |

|

| Lars makes friends with the lizard-monster and lives happily ever after. |

Tuesday, 20 September 2016

If Romantic-Era Artists Ran D&D Campaigns (AKA 'a thin excuse for an image dump')

Giovanni Piranesi (1720-1778): Loves megadungeons. Claims to have run a 'wilderness hexcrawl' once, but this actually just turned out to be a vast network of interconnected dungeons several dozen miles across. His floorplans give the party mapper a headache, but pushing monsters off catwalks never gets old.

Hubert Robert (1733-1808): Took the notes from one of Piranesi's unfinished campaigns and ran with them, eventually developing them into his own distinctive 'ruinworld' setting. His games are much more mellow than Piranesi's, whose version of D&D always seem to devolve into paranoiac nightmare fuel after a couple of sessions.

Heinrich Fuseli (1741-1825): Runs weird, creepy horror campaigns. Uses the 'Insanity Points' system from WHFRP and gives them out like candy. No-one ever has any idea what's going on in his games (partly because their PCs are usually insane), but it always seems to be extremely ominous.

Francisco De Goya (1746-1828): Runs super-disturbing, ultra-violent horror games. Widely agreed to 'have issues'. Keeps 'accidentally' traumatising his players. Most of his games end in TPKs.

.jpg)

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840): Loves wilderness adventures. Claims that all the weird and creepy stuff in his games is 'symbolic'. Won't tell anyone what it's supposed to be symbolic of.

John Martin (1789-1854): Runs non-stop action scenes. Everything is always BIG and EPIC and IN YOUR FACE. His players joke that any time they arrive in a city, it will inevitably be destroyed by invasion, disaster, or the literal wrath of god before the session's end.

Hubert Robert (1733-1808): Took the notes from one of Piranesi's unfinished campaigns and ran with them, eventually developing them into his own distinctive 'ruinworld' setting. His games are much more mellow than Piranesi's, whose version of D&D always seem to devolve into paranoiac nightmare fuel after a couple of sessions.

Francisco De Goya (1746-1828): Runs super-disturbing, ultra-violent horror games. Widely agreed to 'have issues'. Keeps 'accidentally' traumatising his players. Most of his games end in TPKs.

.jpg)

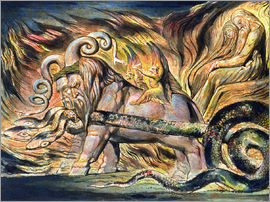

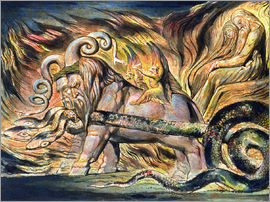

William Blake (1757-1827): The games he runs are super-weird. Once ran seven sessions set in a world inside the heart of a possibly-imaginary guy that the PCs met after Satan invaded their back garden. His players are very, very confused, but the freaky monsters make up for a lot.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840): Loves wilderness adventures. Claims that all the weird and creepy stuff in his games is 'symbolic'. Won't tell anyone what it's supposed to be symbolic of.

| This one is his Fall of Babylon, which really has to be seen full-sized to be believed. (Those tiny white blobs near the middle? Those are war elephants.) You can see a big version here. |

(Reserved for a possible sequel: Joseph Gandy, Samuel Palmer, Eugène Delacroix, John Flaxman, JMW Turner, Benjamin West.)

Sunday, 18 September 2016

A brief public appeal [Non-gaming related]

This post has nothing to do with D&D.

One of the lecturers at my old university has a one-year-old son named Ally. Ally has been diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder called CGD. Unless he can get a bone marrow transplant, he will probably face a life of chronic ill-health followed by an early death. Sadly, no-one currently registered as a bone marrow donor is a close enough genetic match for a successful transplant to take place.

Ally is Korean, which means that the matching transplant he needs will almost certainly have to come from someone of East Asian descent. Unfortunately, the number of East Asian people registered as bone marrow donors is very low.

If you aren't already registered as a potential bone marrow donor, and especially if you are of Korean, Chinese, and/or Japanese ancestry, please consider registering: Ally's family have collected information on how to do this here. Getting your genetic information onto the register is free and quick and painless, and there is a small but real chance that you could end up saving someone's life.

Thank you.

One of the lecturers at my old university has a one-year-old son named Ally. Ally has been diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder called CGD. Unless he can get a bone marrow transplant, he will probably face a life of chronic ill-health followed by an early death. Sadly, no-one currently registered as a bone marrow donor is a close enough genetic match for a successful transplant to take place.

Ally is Korean, which means that the matching transplant he needs will almost certainly have to come from someone of East Asian descent. Unfortunately, the number of East Asian people registered as bone marrow donors is very low.

If you aren't already registered as a potential bone marrow donor, and especially if you are of Korean, Chinese, and/or Japanese ancestry, please consider registering: Ally's family have collected information on how to do this here. Getting your genetic information onto the register is free and quick and painless, and there is a small but real chance that you could end up saving someone's life.

Thank you.

Friday, 16 September 2016

Criminal Man

This is Cesare Lombroso.

Lombroso was a nineteenth-century Italian criminologist who asserted that a great deal of crime was carried out by a class of 'born criminals', which wasn't a very controversial idea at the time. But whereas most criminologists argued that these 'born criminals' were the result of illness or insanity or dyfunctional childhoods or 'degeneration' or other environmental factors, Lombroso claimed that the real truth was much more sinister. The true 'criminal man' was an evolutionary throwback, an atavistic ape-man creature out of the past: you could spot them from their long arms, dark skin, huge jaws, and low, sloping foreheads. They were tall, strong, and usually left-handed, and they had a 'passion for orgies and vendettas'. Evolved to inhabit a primitive world of violence and savagery, they could never live peacefully within the confines of modern civilisation.

If all this sounds creepily proto-Fascist, that's because it totally was. Lombroso even argued that the death penalty was necessary when dealing with such criminals, because they 'are atavistic reproductions not only of savage men but also the most ferocious carnivores and rodents', and that we shouldn't feel pity for them, because 'these beings are members of not our species but the species of bloodthirsty beasts'. It's them or us: 'progress in the animal world... involves hideous massacres', and anyway, they're 'programmed to do harm'. As a result, 'there is no choice but to resort to that extreme form of natural selection, death.'

Is any of this starting to sound familiar yet? Thuggish, primitive, violent, always Chaotic Evil... beast-like, brutal, savage... Lombroso's homo criminalis is basically an orc. He even had his own version of half-orcs: 'criminaloids', who have the same traits in a reduced form, and will thus only commit crimes if a favourable opportunity presents itself. (The true 'born criminal', of course, loves committing crimes so much that he'll commit them under any circumstances whatsoever: 'an opportunity is just a pretext, and they will commit crimes of savage brutality even without it.') What I find interesting, though, is the fact that Lombroso's criminal man doesn't just live 'out there', somewhere, in some God-forsaken wilderness beyond the borders: he is in us. Lombroso's vision of humanity is one where anyone, anywhere, might find themselves unexpectedly giving birth to something that isn't even properly human: the monster is always already inside you, buried at the root of your family tree, waiting to jump back out. Lombroso viewed this as a bad thing. But what if we look at it from the perspective of Criminal Man, instead?

Imagine, for a moment, a scene from a Lombrosan nightmare: the realm of the Crime Kings, tens or hundreds of thousands of years in the past. Here, Criminal Man rules supreme: huge, savage, passionate, immune to pain. Brutal carnivore-men; ferocious rodent-men; weird salamander-men with regenerating limbs. ('Salamanders can reproduce entire limbs... moral madmen possess the ability to heal quickly.') But something has happened: a mutation has occurred. Compared to Criminal Man, the mutants are weak and feeble, and the Crime Kings view them with contempt; but they possess a capacity for self-control and long-term planning which is utterly alien to their bloodthirsty cousins. The mutants are patient: they plot, they scheme, they bide their time. When their plan finally comes to fruition, none of the Crime Kings see it coming.

See them inherit the earth, these soft-skinned mutants. See them hunt the last of the Criminal Men to extinction; see the vanquished homo criminalis dwindle into legends, trolls, hags, ogres, giants, tales with which the victorious mutants might scare their little mutant children at night. Patient, fearful, lacking the grand and honest passion of the Criminal Men, they condemn as wickedness the magnificent feuds and orgies of the past. See the last of the Crime Queens, embittered and alone, knowing the end is at hand. Calling for the last time on the primordial blood-magic of the Crime Kings, she curses the mutants, hiding herself inside their genome. In every generation, they shall bear her children and rear them as their own.

Most die, of course. Born into a world unsuited to them, dragging their huge bodies around like bulls in china shops, hated and hunted and condemned. Their blood calls them to deeds of violence, and they follow its call as faithfully as dogs and are almost always punished for it. They fill the prisons and the asylums. They row in slave galleys. They dangle from gibbets. But they are tough, these children of the Crime Kings. In them is the blood of the rodent-men and the carnivore-men and the salamander-men, the blood the ancient world. Most die. But some of them always survive.

They recognise each other. By their huge jaws and their left-handedness; by their swift healing and their immunity to pain. By their big ears and their huge eye-sockets and their natural aptitudes for stealth and crime. By their 'passion for orgies and vendettas'. By the purity of one another's rages. They gather in gangs, in mafias, in bandit armies. It is always a comfort to them to find one another.

There is a hope inside them, a hope which they do not have the words to articulate.

Sooner or later, a true Crime King will be born to them. And they shall reclaim the earth.

|

| He has analysed your facial measurements, and he finds you degenerate and wanting. Try not to take it personally. |

Lombroso was a nineteenth-century Italian criminologist who asserted that a great deal of crime was carried out by a class of 'born criminals', which wasn't a very controversial idea at the time. But whereas most criminologists argued that these 'born criminals' were the result of illness or insanity or dyfunctional childhoods or 'degeneration' or other environmental factors, Lombroso claimed that the real truth was much more sinister. The true 'criminal man' was an evolutionary throwback, an atavistic ape-man creature out of the past: you could spot them from their long arms, dark skin, huge jaws, and low, sloping foreheads. They were tall, strong, and usually left-handed, and they had a 'passion for orgies and vendettas'. Evolved to inhabit a primitive world of violence and savagery, they could never live peacefully within the confines of modern civilisation.

If all this sounds creepily proto-Fascist, that's because it totally was. Lombroso even argued that the death penalty was necessary when dealing with such criminals, because they 'are atavistic reproductions not only of savage men but also the most ferocious carnivores and rodents', and that we shouldn't feel pity for them, because 'these beings are members of not our species but the species of bloodthirsty beasts'. It's them or us: 'progress in the animal world... involves hideous massacres', and anyway, they're 'programmed to do harm'. As a result, 'there is no choice but to resort to that extreme form of natural selection, death.'

Is any of this starting to sound familiar yet? Thuggish, primitive, violent, always Chaotic Evil... beast-like, brutal, savage... Lombroso's homo criminalis is basically an orc. He even had his own version of half-orcs: 'criminaloids', who have the same traits in a reduced form, and will thus only commit crimes if a favourable opportunity presents itself. (The true 'born criminal', of course, loves committing crimes so much that he'll commit them under any circumstances whatsoever: 'an opportunity is just a pretext, and they will commit crimes of savage brutality even without it.') What I find interesting, though, is the fact that Lombroso's criminal man doesn't just live 'out there', somewhere, in some God-forsaken wilderness beyond the borders: he is in us. Lombroso's vision of humanity is one where anyone, anywhere, might find themselves unexpectedly giving birth to something that isn't even properly human: the monster is always already inside you, buried at the root of your family tree, waiting to jump back out. Lombroso viewed this as a bad thing. But what if we look at it from the perspective of Criminal Man, instead?

| Gaze upon the face of Criminal Man! |

Imagine, for a moment, a scene from a Lombrosan nightmare: the realm of the Crime Kings, tens or hundreds of thousands of years in the past. Here, Criminal Man rules supreme: huge, savage, passionate, immune to pain. Brutal carnivore-men; ferocious rodent-men; weird salamander-men with regenerating limbs. ('Salamanders can reproduce entire limbs... moral madmen possess the ability to heal quickly.') But something has happened: a mutation has occurred. Compared to Criminal Man, the mutants are weak and feeble, and the Crime Kings view them with contempt; but they possess a capacity for self-control and long-term planning which is utterly alien to their bloodthirsty cousins. The mutants are patient: they plot, they scheme, they bide their time. When their plan finally comes to fruition, none of the Crime Kings see it coming.

See them inherit the earth, these soft-skinned mutants. See them hunt the last of the Criminal Men to extinction; see the vanquished homo criminalis dwindle into legends, trolls, hags, ogres, giants, tales with which the victorious mutants might scare their little mutant children at night. Patient, fearful, lacking the grand and honest passion of the Criminal Men, they condemn as wickedness the magnificent feuds and orgies of the past. See the last of the Crime Queens, embittered and alone, knowing the end is at hand. Calling for the last time on the primordial blood-magic of the Crime Kings, she curses the mutants, hiding herself inside their genome. In every generation, they shall bear her children and rear them as their own.

Most die, of course. Born into a world unsuited to them, dragging their huge bodies around like bulls in china shops, hated and hunted and condemned. Their blood calls them to deeds of violence, and they follow its call as faithfully as dogs and are almost always punished for it. They fill the prisons and the asylums. They row in slave galleys. They dangle from gibbets. But they are tough, these children of the Crime Kings. In them is the blood of the rodent-men and the carnivore-men and the salamander-men, the blood the ancient world. Most die. But some of them always survive.

They recognise each other. By their huge jaws and their left-handedness; by their swift healing and their immunity to pain. By their big ears and their huge eye-sockets and their natural aptitudes for stealth and crime. By their 'passion for orgies and vendettas'. By the purity of one another's rages. They gather in gangs, in mafias, in bandit armies. It is always a comfort to them to find one another.

There is a hope inside them, a hope which they do not have the words to articulate.

Sooner or later, a true Crime King will be born to them. And they shall reclaim the earth.

- Criminaloid: AC by armour, 1 HD, +1 to-hit, damage by weapon, saves 14, morale 6. Heal injuries at double normal speed. Criminal skills as per 1st level Thief / Specialist. If confronted with a good opportunity to commit CRIME, must pass a save to resist.

- Homo Criminalis: AC by armour +1, 2 HD, +2 to-hit, damage by weapon +1, saves 13, morale 8. Heal injuries at triple normal speed. Criminal skills as per 3rd level Thief / Specialist. Constantly and compulsively commit CRIME wherever they go.

- Crime King / Crime Queen: AC by armour +2, 6 HD, +6 to-hit, damage by weapon +2, saves 8, morale 10. Regenerate 1 HP per round. Criminal skills as per 9th level Thief / Specialist. Any Criminaloid or Homo Criminalis who is anointed with blood by a Crime King or Crime Queen enters an ecstatic rage for 1d6 hours, during which they gain a +2 bonus to hit, damage, and morale. May possess other forms of ancient crime magic or blood sorcery at GM's option.

Tuesday, 13 September 2016

The sable gold of the taiga: adventures in the early modern fur trade

To everyone except the indigenous peoples who actually lived there, early modern Siberia was about as uninviting as places got: a vast and pathless wilderness of bogs, forests, and tundra which stretched away endlessly to the east of the Ural mountains. For the Russians of the period, the nightmarish months-long journey over the Urals and into the taiga, replete with opportunities for being mauled by bears, mutilated by frostbite, or wandering the forests in circles until you starved to death, was made worthwhile by just one thing - a small, furry thing, about two feet long. The sable.

It's often been remarked that, in many ways, D&D really resembles a Western much more than it resembles medieval Europe. Small communities separated by vast wildernesses; dangerous landscapes roamed by large predators; high levels of tolerance for 'adventurers' and similar social misfits; central authority weak or distant, and probably represented only by the occasional Keep on the Borderlands: all this sounds a lot more like the Old West than, say, thirteenth-century France. In many ways, early modern Siberia (or a fantasy analogue thereof) provides a happy medium between the two. PCs can try their hand at fur trapping, or fur stealing, or hire on as guards to protect someone else's fur stash from raiders or opportunist thieves; they can get mixed up in the regular bouts of violence between the indigenous peoples and the Cossacks who are trying to extort valuable furs out of them at gunpoint; they can map out new paths through the taiga and sell them to the tsar for a fortune; they can get sentenced to convict labour building a road through some godforsaken forest somewhere and have to work out how to escape without getting eaten by bears. Just resist the temptation to replace either the Russians or the indigenous Siberians with non-human races and you should be fine.

The big difference between this and the Old West is the reduced sense of inevitability. The whole mythology of the Western is pervaded by an awareness that the Old West is only ever a transitional moment in history; at the end of the story the cowboy rides west, into the sunset, and in his wake come the railroads and the banks and the lawmen and the big mining companies, turning the mythic Frontier into just another chunk of America. Manifest Destiny marches on: the outlaws or the Apaches can win individual battles, but ultimately they cannot win the war. (I've never studied the actual history, so I've no idea to what extent this is just self-congratulatory fantasy masquerading as historical inevitability, but it's certainly how it's usually presented in the fiction.) But the situation in seventeenth-century Siberia was rather less one-sided: early modern Russia was a ramshackle autocracy rather than a modern industrial state, and its priority was to extract valuable resources from Siberia, not to settle and absorb it. If your PCs decide to ally with a local tribe and stand up to Russian pressure, then if they can make enough of a nuisance of themselves the Cossacks will probably just give up and ride a few hundred miles on in search of someone easier to intimidate. They're adventurers hoping to get rich quick (just like your PCs!), not ideologues out to Tame The Wilderness And Make It Safe For Civilization. One look at a Siberian bog would be enough to convince anyone that that was a terrible idea.

In ATWC, the fur trade is still in its earliest stages. The taiga is gradually being penetrated by strange men from the west, with big beards and big mustaches and really, really big guns. They come in search of furs, and they build forts and roads in lands where no-one has ever built anything more permanent than a yurt before. They make great quest-givers, great trading partners, and great enemies - if I ever did an ATWC monster manual, then 'hairy foreigners with guns' would definitely be one of the entries - but their roads are narrow, and the taiga is immense. For now, at least, they are a curiosity rather than an existential threat.

But they have big plans, and big maps, and they say that their day will come.

| It may be cute, but your PCs will kill it anyway once they find out what its pelt is worth. |

Being smooth, lustrous, and absurdly difficult to get hold of, high-quality Siberian sable furs commanded extremely high prices among the nobility of Persia, China, and Europe. In the Middle Ages, being unable to access Siberia themselves, the Russians had to trade for them with Komi middlemen in the Kingdom of Perm; but the last prince of Perm was deposed by the Russians in 1505, the Russian conquest of the Sibir Khanate from 1580-98 removed the last rival power in the region, and in 1597 the Russian explorer Artemy Babinov charted a new path over the Ural Mountains that allowed much more direct access to Siberia. Over the years that followed, Russian labourers hacked their way through the taiga, gradually changing the Babinov Route from a line on a map into a physical reality on the ground: a road, dotted with Russian forts, along which Russian hunters and fur traders could travel directly into the sable-rich Siberian forests of the east.

The seventeenth-century Siberian fur trade strikes me as being extremely fruitful terrain for gaming, partly because of its many similarities with another setting which almost all players are already going to be familiar with: the American Old West. In each case you have a rising power (Russia / America) pushing beyond its traditional borders to the (east / west) and into new territory, in search of a highly valuable, highly portable luxury good (furs / gold). In each case, obtaining this resource is extremely hazardous: the terrain is hostile and borderline impassable in places, and new infrastructure (roads / railways) are required to open it up for economic exploitation. In each case, there's an indigenous population (native Siberian / native American) who are less than thrilled about all these weird white people turning up in their territories with their guns and their bibles and their interesting new infectious diseases, leading to the construction of a network of forts manned by highly mobile cavalry forces (Cossacks / US cavalry) who are capable of inflicting reprisals on any native groups that step out of line.

| Indigenous Siberian hunter, c. 1700. |

It's often been remarked that, in many ways, D&D really resembles a Western much more than it resembles medieval Europe. Small communities separated by vast wildernesses; dangerous landscapes roamed by large predators; high levels of tolerance for 'adventurers' and similar social misfits; central authority weak or distant, and probably represented only by the occasional Keep on the Borderlands: all this sounds a lot more like the Old West than, say, thirteenth-century France. In many ways, early modern Siberia (or a fantasy analogue thereof) provides a happy medium between the two. PCs can try their hand at fur trapping, or fur stealing, or hire on as guards to protect someone else's fur stash from raiders or opportunist thieves; they can get mixed up in the regular bouts of violence between the indigenous peoples and the Cossacks who are trying to extort valuable furs out of them at gunpoint; they can map out new paths through the taiga and sell them to the tsar for a fortune; they can get sentenced to convict labour building a road through some godforsaken forest somewhere and have to work out how to escape without getting eaten by bears. Just resist the temptation to replace either the Russians or the indigenous Siberians with non-human races and you should be fine.

The big difference between this and the Old West is the reduced sense of inevitability. The whole mythology of the Western is pervaded by an awareness that the Old West is only ever a transitional moment in history; at the end of the story the cowboy rides west, into the sunset, and in his wake come the railroads and the banks and the lawmen and the big mining companies, turning the mythic Frontier into just another chunk of America. Manifest Destiny marches on: the outlaws or the Apaches can win individual battles, but ultimately they cannot win the war. (I've never studied the actual history, so I've no idea to what extent this is just self-congratulatory fantasy masquerading as historical inevitability, but it's certainly how it's usually presented in the fiction.) But the situation in seventeenth-century Siberia was rather less one-sided: early modern Russia was a ramshackle autocracy rather than a modern industrial state, and its priority was to extract valuable resources from Siberia, not to settle and absorb it. If your PCs decide to ally with a local tribe and stand up to Russian pressure, then if they can make enough of a nuisance of themselves the Cossacks will probably just give up and ride a few hundred miles on in search of someone easier to intimidate. They're adventurers hoping to get rich quick (just like your PCs!), not ideologues out to Tame The Wilderness And Make It Safe For Civilization. One look at a Siberian bog would be enough to convince anyone that that was a terrible idea.

| Have fun civilizing this! |

In ATWC, the fur trade is still in its earliest stages. The taiga is gradually being penetrated by strange men from the west, with big beards and big mustaches and really, really big guns. They come in search of furs, and they build forts and roads in lands where no-one has ever built anything more permanent than a yurt before. They make great quest-givers, great trading partners, and great enemies - if I ever did an ATWC monster manual, then 'hairy foreigners with guns' would definitely be one of the entries - but their roads are narrow, and the taiga is immense. For now, at least, they are a curiosity rather than an existential threat.

But they have big plans, and big maps, and they say that their day will come.

Thursday, 8 September 2016

OSR aesthetics of ruin

First off: I know that trying to make generalisations about the OSR as a whole is a fool's errand, and that what I'm actually talking about is less 'the OSR' and more 'that cluster of OSR writers whose works are loosely grouped together by shared connections to Lamentations of the Flame Princess and to each other'. That would make for a rubbish blog post title, though; and I don't think I'd be saying anything too contentious if I was to observe that the group of writers in question have been responsible for a lot of the most high-profile OSR work in recent years. The people I have in mind include (without in any sense being limited to) the likes of Zak S, Gus L, Arnold K, Patrick Stuart, Scrap Princess, Dave McGrogan, Rafael Chandler, Chris Tamm, James Raggi, Zzarchov Kowolski, Bryce Lynch (whose reviews, at this stage, constitute a highly influential body of OSR writing in their own right), James Maliszewski, Patrick Wetmore, Geoffrey McKinney, Clint Krause, Mateo Diaz Torres, Dunkley Halton, Chris McDowall, P. Crespy, and Matthew Finch. And probably a bunch of others whose names are slipping my mind just now.

Each of these writers has a very strong personal voice; but, as I've mentioned before, they also have a strong body of shared aesthetics. One could be boringly reductive and describe it as 'weird science-fantasy horror', but the patterns of imagery which recur throughout their works are actually a good deal more specific than that. More specifically, one of the things which links a lot of them together is a shared interest in the aesthetics of ruin.

Ruins, of course, are central to D&D, and always have been. The original dragon in the original dungeon was Smaug in The Hobbit, who lived in a ruined Dwarven city, and 'it's an ancient ruin' has always been the go-to explanation for why the holy D&D trinity of vast underground complexes, dangerous monsters, and valuable treasure should all be found in the same place. (The basic pitch for many D&D adventures is essentially 'imagine if the Tomb of Tutankhamun had a hundred rooms and half of them were full of killer monsters.') But the ruined-ness of such settings isn't always given much attention; often, the ruin just acts as an excuse for having a dungeon out in the middle of nowhere, with everything and everyone inside it being in a basically non-ruinous condition. The traps are functional. The treasure has retained its full value. The magic items still work. The monsters are in tip-top fighting condition. Even the walls and ceilings are usually in pretty good shape.

In the works of many OSR writers, though, I've noticed that ruin tends to be something which operates on every level: not just in the boringly literal form of physically ruined buildings, but also biological ruins (decaying corpses, malfunctioning ecosystems, unstable mutations, degenerate bloodlines), social ruins (fallen empires, disintegrating social orders, lost knowledge, dying traditions), moral ruins (madness, perversion, fanaticism, corruption), and so on. Their works are full of broken machines that no longer function, lost knowledge which no-one understands, degenerate clans sinking into feral barbarism, once-brilliant minds declining into madness, and scavengers living among the corpses of giants. Their preferred fauna are vermin and scavengers: frogs, snakes, rats, toads, insects, and spiders. Their preferred flora are usually mushrooms and fungi. Frequently-used motifs include rust, cannibalism, insanity, mutation, disintegration, mutilation, and biological decay. Rather than a perfectly healthy tribe of orcs practicing perfectly functional evil magic, their ruin-settings are more likely to be inhabited by clans of mad and degenerate morlocks practicing weird semi-functional cargo-cult sorcery based on badly-misunderstood fragments of ancient knowledge that they found scratched onto the dungeon walls. They don't just live in ruins: they have ruined bodies, ruined minds, ruined societies, and sometimes even ruined souls, as well.

Over and over again, these writers cast the PCs as tiny figures wandering a world of dead and dying titans, stumbling amidst the wreckage of mighty forces they do not understand. (In fact, this could pretty much serve as the plot summary of every LotFP adventure I've ever read.) Whether they're delving into Stuart's Deep Carbon Observatory or Wetmore's Anomalous Subsurface Environment, navigating Gus L's HMS Apollyon or Chandler's Slaughtergrid or McKinney's Carcosa, trying not to die in Crespy's Castle Gargantua or on the slopes of Raggi's Deathfrost Mountain or just about anywhere in Arnold K's Centerra, they are going to be out of their depth and know it. But this is almost never because they're going up against a superior force operating at its full potential; instead, they're usually picking their way through the ruins of something so vast and powerful that even the random flailings of its last malfunctioning machines (or the dwarfish and degenerate descendants of its guard beasts, or the fragmentary and corrupted remnants of its arcane lore) are quite capable of smashing them to bits.

(Look, for example, at the layers of ruination built into the Dragon Hole dungeon that Arnold K is writing right now. A ruined reservoir complex once built to pump water into space, now inhabited by the remnants of a family of dragons, all of whom are insane. Each dragon served by a cult of brainwashed lunatics. The dragon's lair full of broken weapons and crippled would-be dragonslayers. The rotting corpse of their mother at the very bottom. The ruin goes all the way down. Gus L's adventures are even clearer examples of the same thing.)

Andy Bartlett was onto something when, back in 2013, he wrote about the Old School as having a 'pathetic aesthetic' - using 'pathetic' in the old sense of the word, as something capable of arousing feelings of pity or pathos in its audience. But that's only half of it. The fear and vulnerability of its protagonists - and of many of its antagonists, come to that - can and should arouse pathos, although it can also be played for comedy value. But the immense mismatch between their fragile, mortal lives and their huge and ancient surroundings also inspires feelings of awe and grandeur: the aesthetic which used to be known as 'the sublime'. A man bleeding to death in a gutter is pathetic. A man bleeding to death in a gutter in the middle of a pre-human city of mile-high spires combines pathos with sublimity.

(The technical term for the deliberately incongruous combination of sublime and non-sublime elements was 'the grotesque', which is an aesthetic that the OSR also gets a lot of mileage out of. But there's a difference between an aesthetic which deliberately jumbles up high and low elements and an aesthetic which simply places them both on the same stage in order to call attention to the vast disparity between them.)

This 'pathetic sublime' has become a bit of a trademark of much contemporary OSR writing, to the point where it takes a moment to recognise that it's actually a bit counter-intuitive. Real people don't get a choice about whether to encounter a civilisation at its height rather than as an ancient ruin, but authors and GMs do: and if the premise of your set-up is 'something huge once happened here', then why isn't that the focus of the scenario? Why not use a sublime sublime, rather than a pathetic one, and make the PCs as the equals of the world they encounter, mighty men in a mighty age, rather than dwarfish outsiders creeping fearfully through its wreckage? Take something like Gus L's (very good) adventure The Dread Machine. It casts the PCs as adventurers exploring an ancient site which has been stricken with no less than three layers of ruination: the ruin of the empire that built it, the subsequent ruin of the religion that brought that empire down, and the more recent ruin of most of the creatures which once defended it. Why start there, three crashes down the line, rather than having the original baddies up and running in all their evil glory, and the PCs being the Sublime Epic Heroes whose job it is to try to take them down?

Here's where I think it becomes more than just coincidence. Quite apart from their preference for lower power levels, OSR game styles tend to be very open, giving PCs as much liberty as possible to run around an environment and explore it in whatever wildly self-destructive ways they can dream up; but that openness requires and implies a certain set of absences. If PCs can run around the inside of a giant machine pulling levers to see what happens - and they should be able to, because that stuff is classic - then that implies that whoever first built this amazing machine, with all the technological and organisational prowess which its size and complexity implies, is no longer around to stop them. If they can rove from place to place, butchering or befriending the occupants of each area as the whim takes them, then that implies the absence of any kind of overarching authority able to control the movements of this gang of freakish desperadoes. Well-maintained social order is the enemy of free-wheeling adventure, and so the more ruined everything is, the more freedom PCs will have to run around inside it.

(Note that this is much less true of the 'scripted combat encounter' model of play that became the norm in the 3rd and 4th edition eras, where 'break into the fort and fight your way through an escalating series of set-piece battles as the defenders desperately try to repel your invasion' would have been a completely legitimate scenario design. In fact, for adventures like that, too much ruination might well get in the way: you don't want PCs circumventing combat encounters by climbing through the holes in the walls or manipulating the superstitions of the Morlocks, after all...)

I guess what I'm getting at here is that the more wrecked things are, the more open they are to free-form adventure. Malfunctioning AIs, senile liches, mad and delusional immortals, glitching magical security systems... all of these things are open to manipulation in a way that their fully-functional counterparts wouldn't be. Sane and organised beings are going to react rationally, efficiently, and collectively to an intrusion into their territory, which tends to short-circuit adventures; but if they're weird and superstitious and crazy then they can react in much more varied and interesting ways - a possibility which the classic module B4 The Lost City employs to great effect. The World-Shaking Magic of the Ancients probably isn't much use to you in your game: either it actually turns out to be not that much more powerful than anything else, in which case it's going to be a massive disappointment, or it really does have world-shaking power, in which case letting it be used either by or against the PCs is likely to end the campaign. But the fragmentary and poorly-understood remnants of the World-Shaking Magic of the Ancients are great - and precisely because of their ruinous condition, they can be given non-game-ruining effects without actually reducing the mystique of the Ancients themselves. No matter how fantastical something may be, familiarity will breed contempt: but only ever encountering things in fragments prevents them from ever becoming fully known and defined, which is great both for atmosphere and for actually enabling the kind of exploratory gaming which most OSR games are set up to facilitate.

I don't think this is the only reason why ruin is such a prevalent motif in OSR writing. Part of it comes from the rules: if you're a 1st-level character with three hit points exploring a mysterious underworld with dragons and demons in it, then a certain sense of being dwarfed by the world around you is inevitable. Part of it comes from the fascination with horror, which is a genre that was literally born out of people's feelings of discomfort with the ruins of the past. (There's a reason for all those ruined abbeys in early Gothic novels.) A lot of it is inherited from 1920s and 1930s weird fiction writers like Howard and Lovecraft, who were trying to get to grips with the new vistas of 'deep history' revealed by the science and archaeology of the period. But I think the reason that it survives as a design principle, rather than just as an aesthetic choice, is because it actually works for the desired mode of play. 'Five guys take on a fully-garrisoned temple (or castle, or lab, or whatever)' is always going to be either a heist or a commando raid. But 'five guys take on a ruined temple'... Now that can be an actual adventure!

Each of these writers has a very strong personal voice; but, as I've mentioned before, they also have a strong body of shared aesthetics. One could be boringly reductive and describe it as 'weird science-fantasy horror', but the patterns of imagery which recur throughout their works are actually a good deal more specific than that. More specifically, one of the things which links a lot of them together is a shared interest in the aesthetics of ruin.

| 'Jupiter Pluvius', by Joseph Gandy. |

Ruins, of course, are central to D&D, and always have been. The original dragon in the original dungeon was Smaug in The Hobbit, who lived in a ruined Dwarven city, and 'it's an ancient ruin' has always been the go-to explanation for why the holy D&D trinity of vast underground complexes, dangerous monsters, and valuable treasure should all be found in the same place. (The basic pitch for many D&D adventures is essentially 'imagine if the Tomb of Tutankhamun had a hundred rooms and half of them were full of killer monsters.') But the ruined-ness of such settings isn't always given much attention; often, the ruin just acts as an excuse for having a dungeon out in the middle of nowhere, with everything and everyone inside it being in a basically non-ruinous condition. The traps are functional. The treasure has retained its full value. The magic items still work. The monsters are in tip-top fighting condition. Even the walls and ceilings are usually in pretty good shape.

In the works of many OSR writers, though, I've noticed that ruin tends to be something which operates on every level: not just in the boringly literal form of physically ruined buildings, but also biological ruins (decaying corpses, malfunctioning ecosystems, unstable mutations, degenerate bloodlines), social ruins (fallen empires, disintegrating social orders, lost knowledge, dying traditions), moral ruins (madness, perversion, fanaticism, corruption), and so on. Their works are full of broken machines that no longer function, lost knowledge which no-one understands, degenerate clans sinking into feral barbarism, once-brilliant minds declining into madness, and scavengers living among the corpses of giants. Their preferred fauna are vermin and scavengers: frogs, snakes, rats, toads, insects, and spiders. Their preferred flora are usually mushrooms and fungi. Frequently-used motifs include rust, cannibalism, insanity, mutation, disintegration, mutilation, and biological decay. Rather than a perfectly healthy tribe of orcs practicing perfectly functional evil magic, their ruin-settings are more likely to be inhabited by clans of mad and degenerate morlocks practicing weird semi-functional cargo-cult sorcery based on badly-misunderstood fragments of ancient knowledge that they found scratched onto the dungeon walls. They don't just live in ruins: they have ruined bodies, ruined minds, ruined societies, and sometimes even ruined souls, as well.

| Print from Piranesi's 'Carceri'. |

Over and over again, these writers cast the PCs as tiny figures wandering a world of dead and dying titans, stumbling amidst the wreckage of mighty forces they do not understand. (In fact, this could pretty much serve as the plot summary of every LotFP adventure I've ever read.) Whether they're delving into Stuart's Deep Carbon Observatory or Wetmore's Anomalous Subsurface Environment, navigating Gus L's HMS Apollyon or Chandler's Slaughtergrid or McKinney's Carcosa, trying not to die in Crespy's Castle Gargantua or on the slopes of Raggi's Deathfrost Mountain or just about anywhere in Arnold K's Centerra, they are going to be out of their depth and know it. But this is almost never because they're going up against a superior force operating at its full potential; instead, they're usually picking their way through the ruins of something so vast and powerful that even the random flailings of its last malfunctioning machines (or the dwarfish and degenerate descendants of its guard beasts, or the fragmentary and corrupted remnants of its arcane lore) are quite capable of smashing them to bits.

(Look, for example, at the layers of ruination built into the Dragon Hole dungeon that Arnold K is writing right now. A ruined reservoir complex once built to pump water into space, now inhabited by the remnants of a family of dragons, all of whom are insane. Each dragon served by a cult of brainwashed lunatics. The dragon's lair full of broken weapons and crippled would-be dragonslayers. The rotting corpse of their mother at the very bottom. The ruin goes all the way down. Gus L's adventures are even clearer examples of the same thing.)

| Untitled image by Zdzisław Beksiński. If you don't already know his work, you should. |

Andy Bartlett was onto something when, back in 2013, he wrote about the Old School as having a 'pathetic aesthetic' - using 'pathetic' in the old sense of the word, as something capable of arousing feelings of pity or pathos in its audience. But that's only half of it. The fear and vulnerability of its protagonists - and of many of its antagonists, come to that - can and should arouse pathos, although it can also be played for comedy value. But the immense mismatch between their fragile, mortal lives and their huge and ancient surroundings also inspires feelings of awe and grandeur: the aesthetic which used to be known as 'the sublime'. A man bleeding to death in a gutter is pathetic. A man bleeding to death in a gutter in the middle of a pre-human city of mile-high spires combines pathos with sublimity.

(The technical term for the deliberately incongruous combination of sublime and non-sublime elements was 'the grotesque', which is an aesthetic that the OSR also gets a lot of mileage out of. But there's a difference between an aesthetic which deliberately jumbles up high and low elements and an aesthetic which simply places them both on the same stage in order to call attention to the vast disparity between them.)

This 'pathetic sublime' has become a bit of a trademark of much contemporary OSR writing, to the point where it takes a moment to recognise that it's actually a bit counter-intuitive. Real people don't get a choice about whether to encounter a civilisation at its height rather than as an ancient ruin, but authors and GMs do: and if the premise of your set-up is 'something huge once happened here', then why isn't that the focus of the scenario? Why not use a sublime sublime, rather than a pathetic one, and make the PCs as the equals of the world they encounter, mighty men in a mighty age, rather than dwarfish outsiders creeping fearfully through its wreckage? Take something like Gus L's (very good) adventure The Dread Machine. It casts the PCs as adventurers exploring an ancient site which has been stricken with no less than three layers of ruination: the ruin of the empire that built it, the subsequent ruin of the religion that brought that empire down, and the more recent ruin of most of the creatures which once defended it. Why start there, three crashes down the line, rather than having the original baddies up and running in all their evil glory, and the PCs being the Sublime Epic Heroes whose job it is to try to take them down?

|

| More Beksiński. |

Here's where I think it becomes more than just coincidence. Quite apart from their preference for lower power levels, OSR game styles tend to be very open, giving PCs as much liberty as possible to run around an environment and explore it in whatever wildly self-destructive ways they can dream up; but that openness requires and implies a certain set of absences. If PCs can run around the inside of a giant machine pulling levers to see what happens - and they should be able to, because that stuff is classic - then that implies that whoever first built this amazing machine, with all the technological and organisational prowess which its size and complexity implies, is no longer around to stop them. If they can rove from place to place, butchering or befriending the occupants of each area as the whim takes them, then that implies the absence of any kind of overarching authority able to control the movements of this gang of freakish desperadoes. Well-maintained social order is the enemy of free-wheeling adventure, and so the more ruined everything is, the more freedom PCs will have to run around inside it.

(Note that this is much less true of the 'scripted combat encounter' model of play that became the norm in the 3rd and 4th edition eras, where 'break into the fort and fight your way through an escalating series of set-piece battles as the defenders desperately try to repel your invasion' would have been a completely legitimate scenario design. In fact, for adventures like that, too much ruination might well get in the way: you don't want PCs circumventing combat encounters by climbing through the holes in the walls or manipulating the superstitions of the Morlocks, after all...)

| 'Twilight Castle', from Vampire Hunter D. |

I guess what I'm getting at here is that the more wrecked things are, the more open they are to free-form adventure. Malfunctioning AIs, senile liches, mad and delusional immortals, glitching magical security systems... all of these things are open to manipulation in a way that their fully-functional counterparts wouldn't be. Sane and organised beings are going to react rationally, efficiently, and collectively to an intrusion into their territory, which tends to short-circuit adventures; but if they're weird and superstitious and crazy then they can react in much more varied and interesting ways - a possibility which the classic module B4 The Lost City employs to great effect. The World-Shaking Magic of the Ancients probably isn't much use to you in your game: either it actually turns out to be not that much more powerful than anything else, in which case it's going to be a massive disappointment, or it really does have world-shaking power, in which case letting it be used either by or against the PCs is likely to end the campaign. But the fragmentary and poorly-understood remnants of the World-Shaking Magic of the Ancients are great - and precisely because of their ruinous condition, they can be given non-game-ruining effects without actually reducing the mystique of the Ancients themselves. No matter how fantastical something may be, familiarity will breed contempt: but only ever encountering things in fragments prevents them from ever becoming fully known and defined, which is great both for atmosphere and for actually enabling the kind of exploratory gaming which most OSR games are set up to facilitate.

I don't think this is the only reason why ruin is such a prevalent motif in OSR writing. Part of it comes from the rules: if you're a 1st-level character with three hit points exploring a mysterious underworld with dragons and demons in it, then a certain sense of being dwarfed by the world around you is inevitable. Part of it comes from the fascination with horror, which is a genre that was literally born out of people's feelings of discomfort with the ruins of the past. (There's a reason for all those ruined abbeys in early Gothic novels.) A lot of it is inherited from 1920s and 1930s weird fiction writers like Howard and Lovecraft, who were trying to get to grips with the new vistas of 'deep history' revealed by the science and archaeology of the period. But I think the reason that it survives as a design principle, rather than just as an aesthetic choice, is because it actually works for the desired mode of play. 'Five guys take on a fully-garrisoned temple (or castle, or lab, or whatever)' is always going to be either a heist or a commando raid. But 'five guys take on a ruined temple'... Now that can be an actual adventure!