My own personal vision of the WFRP world would be built around nine basic concepts:

1: From above, life in the Old World looks good.

This is an aspect of the setting which was present in the original corebook, but has been mostly neglected ever since. There's a Renaissance in progress! The cities are growing. The economy is booming. The tax receipts are up. Did you see the size of the cannon they wheeled out of the Artillery School the other week? Did you hear how much gold that Tilean treasure fleet carried back from Lustria the other year? (The natives? Who cares about the natives? Just a bunch of stupid lizard-men too dim to realise the value of their own treasure...) The colonies in the New World are multiplying. The land is just there for the taking. We're richer than our forefathers. We're less ignorant. We have printing presses and magnetic compasses and much, much bigger guns. The world is our oyster.

The social elite of the Old World is complacent, not because they're stupid, but because from their perspective everything is going great. They have no interest in hearing the complaints of some ignorant peasant about how bad things are. The ledgers of their bankers tell a very different story.

2: From below, life in the Old World looks terrifying.

Everything's changing. The old certainties are being questioned. The old order is falling apart. People are swarming together into filthy cities where they die in their thousands of waterbourne diseases. There are things lurking in the forests. One of the sewer workers swears he's seen rats down there that walk like men. Lustria is a green hell where the frog-men will shoot you full of poison darts and leave you to bleed out through your own eyeballs while your boss sails off with all the treasure. The New World is a brutal wilderness where half the settlers end up perishing of starvation. When the ships went out last year they found that one of the colonies had just flat-out vanished. The only sign of where everyone had gone was the word NAGGAROTH carved into the side of a tree.

The progress celebrated by the elites is real, but it has been purchased at a terrifying price in social dislocation and human suffering. The poor, unlike the rich, do not have the luxury of ignoring this fact.

3: The threat of chaos is systematically underestimated

The official narrative is that the forces of chaos were vanquished two hundred years ago by Magnus the Pious, and ever since then there's been nothing to worry about. Maybe the occasional cabal of delusional madmen still worships the old chaos gods, but the idea that chaos could still pose a serious threat to civilisation is ludicrous.

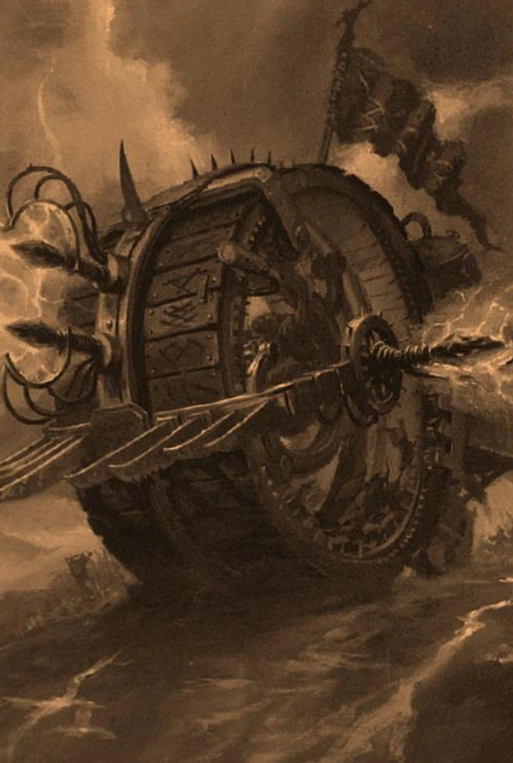

The fact is that chaos has seeped into all the cracks in the Old World's increasingly unstable social fabric. Deep in the woods, in the vast untravelled spaces between the new trade roads, the beastmen have been secretly multiplying for generations, their numbers supplemented by regular influxes of mutants driven out of human communities. In the boudoirs of the very rich, the jaded inheritors of wealth and luxury gather to enact the fashionable blasphemies of Slaanesh. Down in the slums, the truly desperate know that only Fat Father Nurgle can save you once the fevers start. The traumatised veterans of petty wars dream red dreams of a red god on a throne made of human skulls. They gather in psychopathic mercenary companies. They will work for anyone who gives them someone to kill.

'Chaos', in other words, serves as a metaphor for the costs of social change. The authorities ignore it because it suits them to ignore it, but the threat it poses is much greater than anyone recognises.

4: The social order is teetering on the edge of collapse

The Old World is a powderkeg. Think of France on the cusp of the Wars of Religion, or Germany just before the Thirty Years War. The whole society is a mass of barely contained contradictions - rich vs. poor, old vs. new, Ulrican vs. Sigmarite - and it won't take much of a spark to ignite a general conflagration. The feudal order of the Empire, Elector Counts and all, is hopelessly unequal to the task of actually governing the dynamic, rapidly-changing place that the Empire has become. They cling to their outmoded aristocratic trappings as though they still believed that all the world's problems can be solved by a man on a horse with a lance.

A game in this version of WFRP wouldn't have to involve an actual Empire civil war, Empire in Flames style. But the obvious fragility of the social order, and the ease with which acts of sabotage or provocation by the forces of chaos could lead to catastrophe, would be a major theme.

5: The PCs are the people on the margins who can see the world as it is

Rat catchers. Lamp lighters. Sewer jacks. Pamphlet sellers. Grave robbers. Bonepickers. Roadwardens. Bawds. Beggars. Agitators. Gamblers. Outlaws. These people are the protagonists, because they are the only ones in a position to see the truth.

The upper classes can't see it. They've insulated themselves from the world's unpleasant realities.

The lower classes can't see it. They keep to their shops, or their farms, or their workshops. They close the shutters after dark and make a virtue of incuriosity. Bad things happen to people who step out of line.

It's the marginal, semi-criminal classes, right on the edges of society, who are most likely to get glimpses of the truth. The skaven in the sewers. The beastmen in the woods. The ghouls burrowing under the old cemetery. The oddly-proportioned figures who squirm back into the darkness when the lamps are lit. The furtive men and women who gather at the old monolith whenever the moon is dark.

No-one ever wants to hear about what people like the PCs have discovered.

No-one ever wants to hear about what they had to do about it.

And yet, despised and disbelieved as they are, they are often all that stands between human society and the forces that would devour it from within.

6: Adventures take place in the shadows

Hooks are often a weakness in WFRP scenarios, with writers having to come up with all kinds of contrived reasons for why a boatman, a footpad, and a printer's apprentice would ever be picked as the people to deal with the current emergency. In this version, I envision the default adventure as being a bit like Shadowrun meets Call of Cthulhu, with PCs serving as deniable, disposable assets for people dealing with things that they cannot afford to either acknowledge or ignore. When a community leader is confronted with a string of disappearances that the authorities have no interest in solving, or when a cleric needs the disturbing irregularities of one of his colleagues investigated off the books, or when the roadwardens need to know what's eating all these travellers but can't possibly spare any manpower to go riding around in the woods... they reach out to the scum. People with broad minds, strong arms, and empty purses. People who won't scoff at stories of monsters in the sewers, and who won't flinch at risking their lives for a bag of gold and a bottle of rotgut whisky. People like the PCs.

The default PC party would be a friendship group: probably a gang of socially-marginal people who regularly meet up to drink at the same low tavern. They would have a local reputation, not as heroes, but as the sort of people who can get things done for the right price. That should suffice to get them entangled in all kinds of awfulness.

7: Superstition is sometimes right and sometimes wrong

The people used to have a densely-woven fabric of folk beliefs that helped them to survive in the world, but now that fabric lies in tatters, riven by religious reformation and social change. No-one is quite sure what to believe any more. The nobles and scholars may mock them for it, but the people, especially in rural areas, still cling to their beliefs about witches and mutants and the Evil Eye. The clergy bemoan the willingness of the peasantry to indulge the antics of the self-appointed witch hunters who plague the countryside. If only their ridiculous superstitions could be swept away once and for all!

Given the premises this version of WFRP is built around, I think it's really important that sometimes the crazy-looking guy ranting about witches is absolutely right, and sometimes he's just a delusional sadist itching to have the girl next door burned at the stake. The folk beliefs of the people are simultaneously a repository of ancient wisdom unjustly scorned by a complacent elite, and the product of countless generations of shocking ignorance and pointless cruelty, and from the perspective of the PCs it should never be too obvious which is which. The relative tolerance of the authorities towards mutants, for example, should be able to serve both be a metaphor for their increasingly enlightened attitudes towards the kind of people who had previously been the objects of unjust persecution, and for their contemptuous dismissal of the totally valid concerns of the poor. (After all, from the perspective of people like the PCs, why should it be easy to tell the two apart?) The game loses a lot of its bite if 'Burn the witch! Burn the mutant!' is either always right or always wrong.

8: The PCs may be scum, but they are socially mobile scum

This is where the careers system comes in. The world is changing. The old social hierarchies aren't as rigid as they used to be. Just because you're a rat-catcher today doesn't mean you'll be a rat-catcher forever. You just have to keep an eye out for opportunities and make sure you know when to jump ship.

I'd be inclined to couple regular career changes with campaigns that covered long stretches of game time, with months or years between adventures. I'd want the PCs to end up as the kind of people who could say: 'Well, as a kid I worked as a servant, but then in my early twenties I got really angry and became an agitator, except that after a few years things got too hot for me so I ran off into the woods and became an outlaw, but robbing people never really sat right with me so by the time I was thirty I was really more of a vagabond, and life on the road changed my perspective, so when I was thirty-two I took my vows as a friar...' I'd want a real sense that the characters were out there living a life, y'know?

9: The setting is low-fantasy and low-magic

Most people go their whole lives without seeing a non-human. Dark elves are a whispered horror story among New World colonists. High elves are a sailor's tale about an unreachable magical island with a tall white tower. Wood elves are a legend about fae enchanters in the forests. Goblins are a folk tale about the spiteful little creatures who live in caves beneath the hollow hills. Dwarves are proud and distant isolationists, utterly preoccupied with their own long and tragic history that no-one else knows or cares about. Chaos dwarves are a weird lost world civilisation somewhere over the mountains. Magic-using priests and magicians are rare and rather scary figures. (PC magic-users would be fine, but they'd be very much of the 'magical academy student drop-out' type rather than official magi.) Vampires are a horrible rumour in the eastern provinces, rather than the open rulers of Sylvania. Skaven officially don't exist. And so on.

The antagonists for almost all adventures would be criminals, cultists, magicians, religious fanatics, mutants, beastmen, skaven, and the undead. You could probably run a whole lengthy campaign without ever having to decide whether, say, ogres actually existed as anything more than a legend.

Other Miscellaneous bits and pieces

The setting as a whole would be pegged to the mid-seventeenth century, though with plenty of flexibility in either direction. In particular:

- The Empire would be primarily based on Germany just before the Thirty Years War.

- Sylvania would be based on Transylvania during the unsettled years around 1600.

- Marienburg would be based on the Netherlands during its golden age in the mid-seventeenth century.

- Bretonnia would be based on France just before the beginning of the Fronde.

- Norsca would be based on Sweden under Gustavus Adolphus.

- Kislev would be based on Russia under Peter the Great.

- Albion would be based on Britain under James I.

- Estalia would be based on Spain in the early 16th century, in the age of Cortés and Pizarro.

- Tilea would be based on Italy in the early 16th century, in the age of the Medici popes.

I'd use the first edition version of the colleges of magic, with 'colour magic' being a specialised form of magic used by Imperial battle wizards rather than the only form of magic permitted in the Empire. (I'd stick with the second-edition idea of colour magic inducing physical changes in its practitioners, though, which would ensure that the populace at large saw college magicians as little more than state-sanctioned chaos cultists.)

I'd use the religions as detailed in the second edition Tome of Salvation, though with greater emphasis on the Sigmar / Ulric rivalry as the setting's equivalent of the split between Catholics and Protestants. I'd revert the four main chaos gods to their first edition status as 'four examples among many', rather than having them as the great powers of chaos. Malal would be back in. So would the gods of Law.

I'd primarily use the first edition version of Bretonnia, though a shrunken version of second-edition Bretonnia could be included as the setting's equivalent of Brittany. I'd use the second edition versions of Mousillon and Kislev. I'd use the second edition skaven, but I don't think I'd bother with the second edition vampire clans.

I'd keep 'dwarf trollslayer' as a default character type, but would dial back the presence of non-trollslayer dwarves in the setting. I might still have the sea elves hanging around in Marienburg for old time's sake, though. I find the idea of a bunch of elves lolling about in fantasy Amsterdam weirdly appealing.

It would rain all the time. 'Protection from rain' would be the most prized spell in the game.

All PCs would begin play as the owners of small but vicious dogs.