|

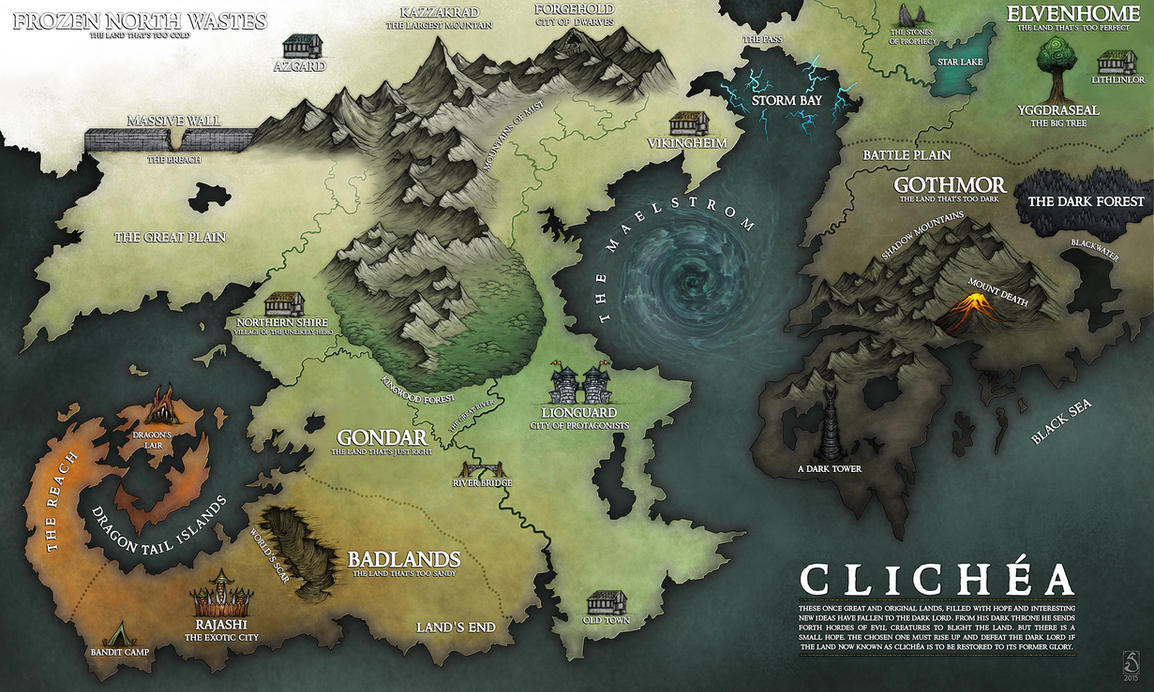

| Map of Clichéa by Sarithus. You can view the full-size version here. |

It's odd how quickly we get used to things. How the fantastical becomes mundane: how the strange and exotic becomes something we take for granted. Think of the tapestry of wonders which make up a generic fantasy world: beautiful forest-dwelling immortals inhabiting hidden cities of living wood and crystal, clans of industrious craftsmen carving out underground kingdoms beneath the earth, blood-crazed tribes of monstrous green-skinned savages who eat the corpses of their enemies, and so on. These figures are the stuff of dreams and nightmares... and yet if the first line of someone's setting write-up starts talking about how the elves are wise and graceful and the eldest of all peoples, I'll drop it in a heartbeat. It's boring. I've seen it a thousand times before.

The trouble is that this applies to everything. I catch myself sometimes talking about 'generic fantasy gods' or 'generic elder evils' or 'generic horror monsters', and I think: how does something designed to be shocking, or numinous, or horrific end up becoming generic? And yet it does: if I open an adventure module and read about a band of insane sorcerers sacrificing victims to the primordial tentacle-covered slime monster who lives beneath their prehuman temple of black basalt, I don't think 'gosh, how awe-inspiringly terrible!' I just think: 'OK, so they're generic fantasy Cthulhu cultists. What else have you got?'

I distinctly remember the moment I fell out of love with World of Warcraft. My quest required me to obtain some bottles of ice water, and the only way to get them was to kill ice elementals, who sometimes dropped them when they died. So there was my gnome assassin, leaping about with her enchanted daggers, hacking her way through gigantic, roaring monsters of living ice in the depths of a frozen chasm beneath a twilight-purple sky, and it was... boring. The game had taken something fantastical and turned it, through sheer force of repetition, into an interaction with a glorified vending machine. All I cared about was whether or not each murdered ice-beast was going to give me a bottle of cold water. I stopped playing the game shortly afterwards.

It's sometimes suggested that the solution to this problem is simply to be more original: to replace your orcs with walrus-men and your dwarves with miniature robot dinosaurs and so on. But as soon as something like this catches on, it can go from being excitingly new to feeling played-out and predictable within just a handful of years. Look what happened to steampunk: it started to really take off around 2005, and by 2012-ish it had already hardened into an almost completely predictable list of visual clichés. (Goggles! Corsets! Top hats and bowlers! Clockwork robots! Airship pirates! Gears on everything! Why aren't you excited yet?) Hell, look at what happened to D&D itself: many of the monsters that people now complain about as 'boring' and 'generic', such as gnolls or drow, were completely new and original back in the 1970s. 'Originality' is a treadmill. Yesterday's shocking new idea is today's mainstream default and tomorrow's tired cliché.

In his 1821 Defence of Poetry, Shelley wrote:

[The language of poets] is vitally metaphorical; that is, it marks the before unapprehended relations of things and perpetuates their apprehension, until the words which represent them, become, through time, signs for portions or classes of thoughts instead of pictures of integral thoughts; and then if no new poets should arise to create afresh the associations which have been thus disorganized, language will be dead to all the nobler purposes of human intercourse.This, I think, is more or less what tends to happen to fantasy elements. They start off as fresh and vivid symbols for urgent realities, or what Shelley calls 'pictures of integral thoughts': orcs were Tolkien's way of articulating the brutalising effects of industrial capitalism, Cthulhu was Lovecraft's symbol for the way in which the cosmos fundamentally doesn't give a fuck about humanity, and so on. Then they get popular, and become 'signs for portions or classes of thought': so Cthulhu gets used as a kind of shorthand for 'A BIG SCARY THING THAT MAKES YOU GO CRAZY', because thanks to Lovecraft we've all somehow come to accept that a giant dragon-man with a squid for a face is an appropriate symbol for that, without it necessarily being connected to any of the things which originally provided the reasons for it to mean that. Soon they become almost entirely symbolic: so a game which features zombies and werewolves and vampires instead of orcs and ogres and dragons will get labelled as 'Gothic horror' instead of 'high fantasy', even if the horror-monsters never actually do anything horrific, because werewolves and vampires are understood to be symbolic of horror in general. And then we play the game and stab all the vampires and wonder why it doesn't actually make us feel afraid.

(You can see these loops playing out with almost comical literalness in games like Pathfinder. You start with a unique monster, like Grendel, and turn it into a type of monster: in this case, the D&D troll. But then the troll gets so overused that it's not scary any more, and no longer conveys the kind of threat communicated by the original. So you go back and you create a new monster, called a Grendel: a mega-troll so strong and powerful that it can terrorise even characters who have become blasé about normal trolls. The diminishing returns involved in such a strategy should be obvious. See also what happens to Dracula in just about every vampire fiction franchise.)

When fantasy fails to feel fantastic, I think it's often because its creators use these fantastical elements as shortcuts or placeholders, relying on their inherited symbolic associations to do all the imaginative heavy lifting. They rely on an audience which is going to find the very idea of dragons so awesome that they'll love your story just for having dragons in it, even if your dragons never actually do anything very impressive, or very dragon-like, or even very interesting. But the more familiar your audience is with the genre, the less credit they're going to give your work just for including orcs and elves and whatnot, because for them those figures will be part of a symbolic system which has been drained of all its inherent power by overuse.

So don't do that. Don't just rely on the fact that something is a troll to convey the fear and the power of it: maybe that would have worked a hundred years ago, but now they've been so drained of significance that your players are just going to see them as big bags of hit points with annoying regenerative abilities. Instead, you have to reconnect them with whatever it was that gave them force and meaning in the first place. 'A goblin' is a three hit point irritation. A giggling thing with too-long arms and a too-wide mouth and far too many teeth that comes squirming out from under your bed at night to cut you up with knives is fucking terrifying. 'An ogre' is a big dumb lump for your PCs to kite around a battlefield. An eight-foot giant who comes clambering from her cannibal larder, her hot breath reeking of carrion, her long hair matted with human gore, still retains some level of nightmarish power. At this point, the names have probably become active liabilities: the howling abhuman beast that roams the wastelands, larger and more savage than any man, becomes much less threatening once it has been identified as 'an orc' or 'a bugbear' or 'a troll'. You don't need to wear yourself out trying to come up with totally original, never-before-seen ideas in every damn adventure: after all, the classics are classics for a reason. You just need to make sure that, when you use the classics, you go right back to the source.

Because the stories never truly lost their power. Not really. There's still something magical about the glimpse of the path through the woods at twilight, or the huge figure unfolding itself from the cavern in the hillside, or the whispering and scurrying of swift and unseen creatures in the dark. The shining city on the distant hilltop. The sound of something slow and heavy moving through the forest by night. It would be a shame if we let the overuse of our shared shorthand of fantasy iconography stand between us and the very real wellsprings of awe and terror which are, at base, still represented by those symbolic figures with which we have become so painfully over-familiar.

Orcs. Elves. Ogres. Giants.

eotenas ond ylfe ond orcnéäs

swylce gígantas þá wið gode wunnon

lange þráge· hé him ðæs léan forgeald.