|

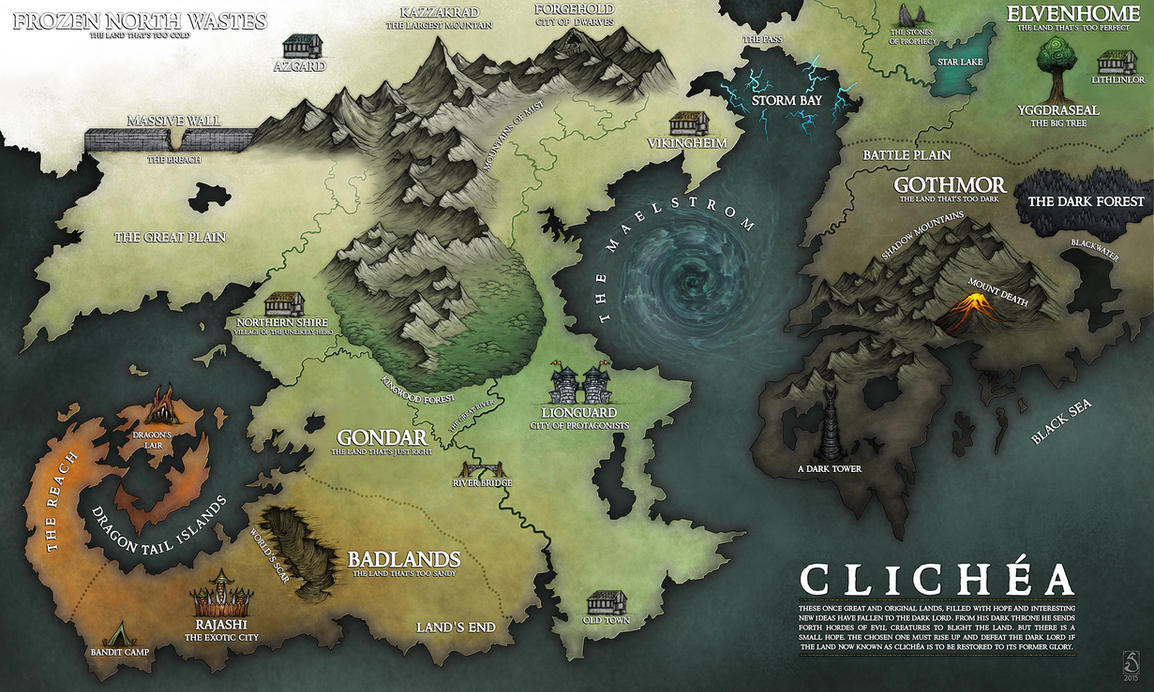

| Map of Clichéa by Sarithus. You can view the full-size version here. |

It's odd how quickly we get used to things. How the fantastical becomes mundane: how the strange and exotic becomes something we take for granted. Think of the tapestry of wonders which make up a generic fantasy world: beautiful forest-dwelling immortals inhabiting hidden cities of living wood and crystal, clans of industrious craftsmen carving out underground kingdoms beneath the earth, blood-crazed tribes of monstrous green-skinned savages who eat the corpses of their enemies, and so on. These figures are the stuff of dreams and nightmares... and yet if the first line of someone's setting write-up starts talking about how the elves are wise and graceful and the eldest of all peoples, I'll drop it in a heartbeat. It's boring. I've seen it a thousand times before.

The trouble is that this applies to everything. I catch myself sometimes talking about 'generic fantasy gods' or 'generic elder evils' or 'generic horror monsters', and I think: how does something designed to be shocking, or numinous, or horrific end up becoming generic? And yet it does: if I open an adventure module and read about a band of insane sorcerers sacrificing victims to the primordial tentacle-covered slime monster who lives beneath their prehuman temple of black basalt, I don't think 'gosh, how awe-inspiringly terrible!' I just think: 'OK, so they're generic fantasy Cthulhu cultists. What else have you got?'

I distinctly remember the moment I fell out of love with World of Warcraft. My quest required me to obtain some bottles of ice water, and the only way to get them was to kill ice elementals, who sometimes dropped them when they died. So there was my gnome assassin, leaping about with her enchanted daggers, hacking her way through gigantic, roaring monsters of living ice in the depths of a frozen chasm beneath a twilight-purple sky, and it was... boring. The game had taken something fantastical and turned it, through sheer force of repetition, into an interaction with a glorified vending machine. All I cared about was whether or not each murdered ice-beast was going to give me a bottle of cold water. I stopped playing the game shortly afterwards.

It's sometimes suggested that the solution to this problem is simply to be more original: to replace your orcs with walrus-men and your dwarves with miniature robot dinosaurs and so on. But as soon as something like this catches on, it can go from being excitingly new to feeling played-out and predictable within just a handful of years. Look what happened to steampunk: it started to really take off around 2005, and by 2012-ish it had already hardened into an almost completely predictable list of visual clichés. (Goggles! Corsets! Top hats and bowlers! Clockwork robots! Airship pirates! Gears on everything! Why aren't you excited yet?) Hell, look at what happened to D&D itself: many of the monsters that people now complain about as 'boring' and 'generic', such as gnolls or drow, were completely new and original back in the 1970s. 'Originality' is a treadmill. Yesterday's shocking new idea is today's mainstream default and tomorrow's tired cliché.

In his 1821 Defence of Poetry, Shelley wrote:

[The language of poets] is vitally metaphorical; that is, it marks the before unapprehended relations of things and perpetuates their apprehension, until the words which represent them, become, through time, signs for portions or classes of thoughts instead of pictures of integral thoughts; and then if no new poets should arise to create afresh the associations which have been thus disorganized, language will be dead to all the nobler purposes of human intercourse.This, I think, is more or less what tends to happen to fantasy elements. They start off as fresh and vivid symbols for urgent realities, or what Shelley calls 'pictures of integral thoughts': orcs were Tolkien's way of articulating the brutalising effects of industrial capitalism, Cthulhu was Lovecraft's symbol for the way in which the cosmos fundamentally doesn't give a fuck about humanity, and so on. Then they get popular, and become 'signs for portions or classes of thought': so Cthulhu gets used as a kind of shorthand for 'A BIG SCARY THING THAT MAKES YOU GO CRAZY', because thanks to Lovecraft we've all somehow come to accept that a giant dragon-man with a squid for a face is an appropriate symbol for that, without it necessarily being connected to any of the things which originally provided the reasons for it to mean that. Soon they become almost entirely symbolic: so a game which features zombies and werewolves and vampires instead of orcs and ogres and dragons will get labelled as 'Gothic horror' instead of 'high fantasy', even if the horror-monsters never actually do anything horrific, because werewolves and vampires are understood to be symbolic of horror in general. And then we play the game and stab all the vampires and wonder why it doesn't actually make us feel afraid.

(You can see these loops playing out with almost comical literalness in games like Pathfinder. You start with a unique monster, like Grendel, and turn it into a type of monster: in this case, the D&D troll. But then the troll gets so overused that it's not scary any more, and no longer conveys the kind of threat communicated by the original. So you go back and you create a new monster, called a Grendel: a mega-troll so strong and powerful that it can terrorise even characters who have become blasé about normal trolls. The diminishing returns involved in such a strategy should be obvious. See also what happens to Dracula in just about every vampire fiction franchise.)

When fantasy fails to feel fantastic, I think it's often because its creators use these fantastical elements as shortcuts or placeholders, relying on their inherited symbolic associations to do all the imaginative heavy lifting. They rely on an audience which is going to find the very idea of dragons so awesome that they'll love your story just for having dragons in it, even if your dragons never actually do anything very impressive, or very dragon-like, or even very interesting. But the more familiar your audience is with the genre, the less credit they're going to give your work just for including orcs and elves and whatnot, because for them those figures will be part of a symbolic system which has been drained of all its inherent power by overuse.

So don't do that. Don't just rely on the fact that something is a troll to convey the fear and the power of it: maybe that would have worked a hundred years ago, but now they've been so drained of significance that your players are just going to see them as big bags of hit points with annoying regenerative abilities. Instead, you have to reconnect them with whatever it was that gave them force and meaning in the first place. 'A goblin' is a three hit point irritation. A giggling thing with too-long arms and a too-wide mouth and far too many teeth that comes squirming out from under your bed at night to cut you up with knives is fucking terrifying. 'An ogre' is a big dumb lump for your PCs to kite around a battlefield. An eight-foot giant who comes clambering from her cannibal larder, her hot breath reeking of carrion, her long hair matted with human gore, still retains some level of nightmarish power. At this point, the names have probably become active liabilities: the howling abhuman beast that roams the wastelands, larger and more savage than any man, becomes much less threatening once it has been identified as 'an orc' or 'a bugbear' or 'a troll'. You don't need to wear yourself out trying to come up with totally original, never-before-seen ideas in every damn adventure: after all, the classics are classics for a reason. You just need to make sure that, when you use the classics, you go right back to the source.

Because the stories never truly lost their power. Not really. There's still something magical about the glimpse of the path through the woods at twilight, or the huge figure unfolding itself from the cavern in the hillside, or the whispering and scurrying of swift and unseen creatures in the dark. The shining city on the distant hilltop. The sound of something slow and heavy moving through the forest by night. It would be a shame if we let the overuse of our shared shorthand of fantasy iconography stand between us and the very real wellsprings of awe and terror which are, at base, still represented by those symbolic figures with which we have become so painfully over-familiar.

Orcs. Elves. Ogres. Giants.

eotenas ond ylfe ond orcnéäs

swylce gígantas þá wið gode wunnon

lange þráge· hé him ðæs léan forgeald.

I recommend grabbing a copy of Rafael Chandler's Teratic Tome. From my review (http://www.kjd-imc.org/blog/review-teratic-tome-by-rafael-chandler/):

ReplyDeleteThe content, though? Scary monsters. I don’t mean high-level threats, though the book is heavily weighted that way. I don’t mean difficult Armor Class and high damage attacks. I mean monsters that actually evoked visceral “oh my gods I don’t want to meet one of those” reaction in me.

The kind where just one of these creatures could legitimately raise an “oh shit, that’s what happened! Is it still around?!” reactions in players when they discover what’s been going on. Or possibly better yet, “that is what is happening, can we stop it?!” reactions.

I've read the Teratic Tome. I'm not so fond of the fact that so many of the monsters exist purely to hurt people - I prefer creatures which can be communicated with over things that just have to be killed - but Chandler certainly knows how to create some memorably grotesque murder-monsters!

DeleteHe was aiming for that, he hit it. I don't use the monsters in Teratic Tome all that often, and I think never from Lasus Naturae.

DeleteMore importantly to this discussion, though, is how he describes the monsters (http://www.kjd-imc.org/blog/teratic-monster-design/).

* They are Inhuman

* They are Grounded in the Setting

* There is Nothing Quite Like Them

* They are Identifiable Even When Not Present

You don't have to make them as viciously murderous, but the points above can help make them stand out.

I took a run at touching up goblins, starting with the Pathfinder bestiary description and applying the teratic design principles above.

Deletehttp://www.kjd-imc.org/blog/teratic-tome-takeaways/

I agree that going back to the source material can bring back the magical nature of those original horrific descriptions. But it often feels like a losing battle.

ReplyDeleteI've been able to instill some anxiety back into my players by withholding "it's a goblin," and only describing it's mottled purple skin encrusted with fungus and rot. I say anxiety because that's really the best you'll get in a scary scenario. Rarely are players truly afraid. It worked for a while, but their anxiety gave way to frustration because they still didn't know what these things were. It was fun for the first few rounds of combat, but it became "unhealthy" by the third or fourth round.

Players will always create categories for things, or at least mine will. No matter how hard I try, the description based method you advocate for becomes inefficient, or worse, ineffective. It's worked well for lone monsters they've encountered in the dark, but that's about it. I'm not entirely sure where I'm going this, so I apologize for the rambling of this comment.

No need for an apology! And, yes, of course they'll create categories: it's what humans do. My point is more that you just need to keep close to the sources of whatever it is that makes this thing scary (or awe-inspiring, or whatever). Never let them fade into being 'just' goblins.

DeletePearce Shea wrote some very good stuff on this here:

http://gameswithothers.blogspot.co.uk/search/label/horror

I dunno, you say it's worked for solitary/one-off monsters, giving them a certain mystique... as for repeats like your goblins, it's natural they're going to become 'a known factor' at some point. That's unavoidable and nothing really wrong with it. Like, you might freak out the first time worrying the little blighters were carrying some disease, but after a few skirmishes you're more comfortable killing them up close, etc.

DeleteI mean, if they're not dangerous then they're not dangerous, and the PCs will work that out sooner or later. The point is not to deceive the players. It's just to make sure that the fantasy elements you use aren't short-changed of whatever threat or power they might otherwise possess!

DeletePerhaps as much as familiarity, it is the lack of risk of the PC dying, the lack of sense of danger? Or worse,the lack of not caring if the character dies? Anxiety and tension is needed. No danger, no tension.

ReplyDeleteI think that's true, and that it goes beyond just the straightforward relationship between fear and the risk of character death. A certain sense of *vulnerability* to the world can go a long way towards making that world seem larger, weightier, more meaningful - and that, in turn, makes all kinds of emotions easier to inspire. But that may just be my preference for lower-powered play at work... and, of course, no amount of vulnerability will inspire fear (or anything else) without player buy-in. The line between horror and absurdist comedy is thin at the best of times, after all...

DeleteI agree with your assessment, Joseph, but I'm not sure what someone could actually do about this. I can see two possible solutions.

ReplyDeleteFirst, maybe you could just ditch the names, and just describe the monsters. These aren't Orcs, they're green cannibal monster men. If the players want a name for these things, they can name the monster themselves, or go investigate. However, this could just be a bandage on a gaping wound

Secondly, maybe one could lean into this fact? Make all your Vampires sensitive to the fact that they're perceived more of as sex symbols than monsters, and all your Werewolves are hunky wild-men, with oiled abs and shaggy beards. Though that also doesn't seem like something that would work in a more serious game.

Thirdly, I think that originality is still the best defense. If you're going to write an adventure about discovering something new and you want to include a Vampire, have 1, maybe 2 Vampires in the adventure. Then, next time you go to write an Adventure, don't write about Vampires.

1 and 3 are certainly good tactics. I don't hold religiously to the LOTFP principle that 'the monsters in every adventure should be unique', but I think it definitely points in the right direction. Making sure that your players are constantly encountering new things, and that they don't necessarily have a clear idea of what those things are or what they're capable of, is a good way to keep them from getting too comfortable with the world.

DeleteLike I say in the post, though, I don't think you *need* to do that. I think you just need to figure out what makes your fantasy elements work and really push on that. A cave full of goblins played as nightmare murderers in the dark will create a much more powerful effect than a cave full of super-original horror monsters played as dumb bags of hit points!

I avoid naming monsters and rely on imagery. This helps, especially with newer players, but there is a sacrifice of verisimilitude. In a world populated with actual ogres, you'd better bet that people would be able to identify them by name at a glance or even via smell or spoor. I trade away that slice of realism for wonder, but it still galls a little.

ReplyDeleteWell, they might or they might not. If ogres are as common as, say, bears are in our world, then of course they would. But if there are only a handful of them, or if they live in some very remote region, them reports of their appearance might be as contradictory as reports of cryptids are in our world today.

DeleteSecondly... while I agree that having a name for a thing can lessen its power, granting a spurious sense of understanding and mastery, encountering the thing itself can still have considerable impact. (Think how different reading about an animal on wikipedia is from encountering one in the wild!) Again, I think the trick is to identify what makes them work, symbolically, and then really push on that. If your ogres are sufficiently powerful and hungry and brutal then they should generate a pretty overwhelming impression even on players who do have a name for them!

I would point out that what the monsters do can be part of the solution. After all, we are pretty familiar with humans, but its still possible to make them scary as hell.

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely! And this is the thing that gets me - all the things that should make fantastical creatures *more* imaginatively powerful than humans very often actually serve to make them *less* so. When an orc or a troll is *less* scary than a regular human murderer, then surely something has gone wrong somewhere...

DeleteOne idea is not to name the monsters in your campaign for the players, even after they are killed. Become more interesting in how you describe them, vary how you describe the same creature.

ReplyDeleteUse of language is key. One of the reasons I despise the use of random tables as a crutch is that there is *zero content* in the flabbergasting jumble of words, but people think nouns or names by themselves carry weight. If you can't make a goblin come alive, or a psychopathic cultist you sure as hell won't make a human character come alive and that is pathetic.

Yes - again, no-one questions that *humans* can be scary, or tragic, or awe-inspiring, and so on. With all the resources of the imagination to call upon, it should be *easier* rather than harder to have fantastical creatures and situations evoke those feelings. That's what most of these creatures are, at base, after all: just humans hyperbolically exaggerated in one direction. That hyperbole should be an imaginative *resource*, not a limitation!

DeleteI did a reskinned Weird Western game once involving all sorts of threats from bandits to dinosaurs to warlocks of Santa Muerte, and the encounter that seemed to be the most terrifying was a ranch house infested by goblins.

ReplyDeleteGoblins after the style of Anthony Boucher's "They Bite" and the remake of "Don't Be Afraid of the Dark."

Glimpses in the peripheral vision. A scuttling sound under the floorboards. A chicken left as bait in a trap; the players went around a corner and came back to find the trap sprung and nothing but feathers left. A character looked under a bed and got just a glimpse of something like a mummified monkey that struck like a snake and bit a chunk out of his face. Blood all over the floor. The characters retreated to regroup, and when they came back, the floor had been licked clean. They had faced much, much more dangerous things, but wanted nothing to do with those spindly little creeps ever again.

Yeah, that's a great example! And I think that you could do something similar for most other monsters, with a bit of work...

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeletemost of my players are 20+ years veterans. while i agree with almost everything you wrote, i can not escape the notion that maybe as a dm you have to adjust for the fact that your players are grizzled veterans even if their characters are greenhorns.

ReplyDeleteIt was the veterans I had in mind, honestly. For new players, the wow factor of 'I'm a dwarf! In a cave!! Fighting goblins!!!' is still likely to be mostly intact...

DeleteThe source material definitely helps. Reading Three Hearts and Three Lions helped me understand D&D trolls better; the one encounter with a troll there is essentially an ambush (by the troll) - they're not going to attack out in the open, they're going to try to hit first and absorb any retaliation, then hide again to heal before striking again.

ReplyDeleteThis is an issue that goes way beyond RPG but affects all fantastic fiction as a whole.

ReplyDeleteIt's a rare day that I feel I completely understand what someone said about poetry two centuries back, and even more so that I completely agree with it. But Shelly's quote seems to match exactly what came to my mind after reading the first paragraphs that outlined the question. You can't just put something into a work and expect it to be great because it has been a great part in other works. Images and symbols only work if you use them to create an effect. To be the "pictures of integral thoughts".

I am a bit surprised to see the exact problem with contemporary fiction being examined in the 19th century. But then again, it's not surprising at all. In the long history of fantasy, why would this be anything new?

Well, Shelley was mostly thinking about epic poetry, which had the same problems in 1820 that fantasy has today: people just wrote long poems stuffed full of things they'd copied from Homer, Virgil, and Milton, and then wondered why the resulting works turned out to be unreadable. They had their version of the 'originality treadmill', too, in the form of writers who tried drawing on new mythologies instead, leading to epics like 'Thalaba the Destroyer' (Arabian-inspired) and 'The Curse of Kehama' (Indian-inspired). But I think the situation is analogous - indeed, I think the modern fantasy genre is in some ways an outgrowth of the Romantic-era epics that Shelley had in mind...

DeleteNice article, thank you. Shelley's quote reminded me of this quote from CS Lewis:

ReplyDelete"Even in literature and art, no man who bothers about originality will ever be original: whereas if you simply try to tell the truth (without caring twopence how often it has been told before) you will, nine times out of ten, become original without ever having noticed it."

Here, by "bothering with originality" he means, I think, trying to be novel for novelty's sake. A detail that grows out of that kind of fussy, self-conscious originality ("yes, but THESE are *orqs* with a "q" and they have white skin not black... bet you didn't see that coming heh heh") is fluff at best and tedium at worst. But like you say, if you go back to the deep source of various tropes, and create from that place, the details that pop up along the way often become integral and surprising and yes, original, in a way that feels fresh and exciting and true.