Severed Fane asked for a 'small campaign bible' for my current campaign, City of Spires, which shares a setting with my previous Team Tsathogga campaign. This campaign world started as a kitchen-sink-y science fantasy setting, suitable for running short, casual games over beer with players new to D&D. To my utter astonishment, I'm still running games set in the same world six years later, and it has now accumulated a staggering level of background lore.

What follows is a very zoomed-out version of the setting. Obviously I can't include anything that my PCs haven't discovered yet, but this post provides a snapshot of the discovered regions of the setting as they currently stand, fifteen years of game-time after our first campaign began!

Deep history: City of Spires, like Team Tsathogga before it, takes place on the world originally known as Research Planet Alpha Three. It was colonised thousands of years ago by a spacefaring empire of serpent men, who used it as a research base for something called 'The God-Mind Project': this seems to have involved going to other planets, capturing the various god-like psychic 'hyper-intelligences' they found there, and bringing them to Alpha Three in a limbo state of [sleep / death / non-existence] for research purposes. Presumably this was eventually going to lead to some kind of pay-off for the empire, but their civilisation was destroyed in an interplanetary slave uprising before their work could come to fruition.

Even before their empire fell, the serpent-men on Alpha Three were not much involved in the day-to-day running of the colony. In the part of the planet in which the campaign is set, the various species they imported or created were ruled for them by three client states: the Zaant Imperium (ruled by island-dwelling ape-men), the Omen Kingdom (ruled by one-eyed giants), and the Nameless Empire (ruled by human magicians - its name is genuinely lost, having apparently been burnt out of history by some terrible magic). When the empire fell apart, a rebel space fleet obliterated the main power centres of these loyalist states from orbit. The rebels were then meant to land and liberate their enslaved subjects, but something happened and the liberating army never came. What went wrong with the rebellion, like the purpose of the God-Mind Project, has been one of the major mysteries behind both campaigns.

The game is set 1300-ish years later.

The Chaos Ages: The destruction of the serpent man power structure, coupled with the non-appearance of the rebel army, ushered in an age of chaos. The magitech infrastructure of the old empires fell apart, and the world was ravaged by the various war machines, monsters, and bioweapons released, intentionally or otherwise, during the war. Power in many regions was seized by local warlords who managed to salvage fragments of functional magitechnology from the general conflagration: these included the Witch Queens, the Cannibal King, the Scavenger Lords of Aram, and the Kings of Ruin. Other regions fell under the sway of cults worshipping the alien hyper-intelligences kidnapped by the God-Mind project, whose containment systems were shattered by the war, leaving them leaking incoherent psychic distress into the surrounding world. This was a pretty grim era, remembered in most places as a dark age of strife now thankfully surpassed.

The modern era: In the end the various Chaos Age despotisms mostly destroyed each other, or were overthrown by their subjects, or simply disintegrated when their scavenged relic technology finally degraded into uselessness. In their place came more stable polities, unified by pro-social religions such as the worship of the Bright Lady (a deified folk memory of the original rebel commander), the Shining Ones (pure-energy beings imprisoned by the serpent folk to power their magitech infrastructure), and the Golden Lotus (a transcendent embodiment of cosmic Law). The God-Mind cultists, who despite their formidable supernatural powers tended to be a crazy and dysfunctional bunch, were mostly driven into the wilderness.

Today a range of nations have arisen in the more habitable areas of the old empires. However, the areas beyond their borders are still littered with radioactive ruins, magical dead zones, and the lairs of weird creatures who escaped from the prisons and laboratories of the serpent men.

Regions visited so far

Qelong: Based on the (excellent) supplement of the same name, this Khmer-inspired nation was saved from utter ruin by the PCs during the first campaign and is now staggering back towards something resembling normality, although vast swathes of the hinterland remain effectively post-apocalyptic. The Naga who empowers the river flowing through it was one of the victims of the God-Mind project, and is presumably imprisoned somewhere beneath the nation.

The Cold Marshes: Freezing expanse of marshlands inhabited by mutated marsh giants, and by human tribes who ride upon great swamp beasts and drive squirming masses of bog mummies into battle by beating on enchanted drums. The PCs in the first campaign kidnapped one and forced him to give them drumming lessons.

The Stonemoors: A windswept land of sheep-herding crofters brought to crisis when the perpetual snowfall ceased on its holy mountain, denying meltwater to its rivers and causing a serious drought. (This turned out to be due to the theft of an enchanted maiden from the mountain, who had been slumbering in suspended animation within a magitech casket.) In desperation, the hardest-hit clans turned to a cave-dwelling monster, the Blood Fiend, for power to extort food their neighbours. In the first campaign the PCs found the casket but kept it as a power-source for their flying ship, and 'solved' the problem by sending the Blood Fiend and his followers off to reclaim the Fiend's birthplace in the Grey Uplands.

The Plateau of Yeth: Inspired by Minotaurs of the Black Hills by Raging Swan Press. Plateau inhabited by minotaur clans, who arrived here as invaders, but whose power was broken by the terrible heat-weapons of the bat-folk who lived within the citadels of vitreous stone at the plateau's heart. Since then they have lived humble lives as tributaries of the bat-folk, whose skill in technology remains great, but whose numbers have now waned to the point that their citadels are almost empty. The PCs from the first campaign adopted one who had aspirations of reversing the decline of his people, but then apprenticed him to a mad scientist and forgot about him.

The Great Northern Wilderness: Vast expanse of hills and forests inhabited mostly by savage cave dwarves and mad vulture-men, who once ruled as death-priests of the necromantic Carrion Kingdom until their defeat by the bat-folk of the Plateau of Yeth. Hidden here are the Pools of Life (loosely based on Dwimmermount), an ancient complex where the serpent men originally created their 'demon' shock troopers. An attempt to duplicate this feat by a sorcerer in the Chaos Ages led to the creation of the minotaurs, who were the closest he could manage to the real thing, but who soon turned on their creator. Later still the Pools were looted by a magician in the service of the Church of the Bright Lady, who went rogue and used his stolen technology to create the creatures of the Grey Uplands. In the first campaign the PCs shut down the complex and its malfunctioning monster-engines, and led the creatures trapped within it back into the light.

The Grey Uplands: Remote upland region inhabited by the various monsters created using magitechnology stolen from the Pools of Life - including the Blood Fiend, who later ran off to the Stonemoors. In a castle at its centre lived an isolationist settlement of humans with transparent skin, bred for medical testing purposes. The PCs in the first campaign evacuated the humans to a haunted valley they'd found earlier, and sent the Blood Fiend and his followers back to reclaim their homeland.

The Purple Islands: Inspired by Islands of Purple-Haunted Putrescence. Taken over by the PCs during the first campaign, now the home of a motley assortment of humans, apemen, and undead practising a syncretic religion that the PCs invented. Contains a lot of relatively intact ruins due spending most of the last four hundred years outside the timestream. There was once a hidden Serpent Man science base here, but the PCs invaded it and killed most of them, with the ones that got away vanishing into the jungles of the south.

Reval: This temperate agricultural kingdom is the seat of the Church of the Bright Lady, which is run by mysteriously similar-looking 'Angels' and an all-female council of Elders who appear to be mutants of some kind. Site of Glasstown, home of the setting's leading magical academy, which has some kind of sinister dealings with the Mirror Men. Recently ravaged by a plague of 'demons' falling from the sky - these turned out to be genetically-engineered warriors created by the serpent men, who had been floating in orbit in their cryo-chambers since the empire's fall. In the first campaign the PCs discovered their ancient command codes, and managed to free some of them from servitude.

The Underworld: A vast expanse of caverns beneath Reval inhabited by many strange monsters, including goblins and toad-folk loyal to Tsathogga, who was one of the beings kidnapped for the God-Mind project and is presumably imprisoned somewhere down there. The dominant underworld powers were previously the Science Fungoids and the Navigator Houses of the Nightmare Sea (which I lifted from They Stalk the Underworld and False Machine, respectively), but in the first campaign the PCs inflicted terrible damage upon the Science Fungoids, allowing the Navigator Houses to establish trade relations with the surface and press everyone nearby into debt slavery.

The Grand Duchy: Cold northern nation, remote and agriculturally poor, a centre of the fur trade. Plagued for years by the Devourer cultists hidden in the mountains, who secretly served the serpent men of the Purple Islands, drawing liquid time from a sleeping titan buried in the earth (another God-Mind project victim) and using it to keep the Purple Islands isolated from the timestream. It was the fall of this cult that precipitated the reappearance of the Purple Islands and the rain of 'demons' in Reval. The PCs in the first campaign ransacked the cult temple, and adopted the undead cultists they accidentally awoke while doing so, leading them back to the Purple Islands.

Ingra: A fertile land of shady, forested hills and valleys, once a stronghold of the Witch Queens until their defeat by the followers of the Bright Lady. Witch-cults and beastmen still lurk in its deeper forests. Its cities are famous as centres of learning, and especially renowned for their schools of medicine. A secret society, the Cult of the Divine Surgeon, commands the loyalty of many senior doctors and academics, revering an obscure golden-armed hero figure from the early Chaos Ages.

Aram: Once a hub of trade between the eastern and western nations, now in decline since the Howlers cut off the roads to the east. Centre of the faith of the Shining Ones, whose holy city was once the capital of the Nameless Empire. Reliant on alchemically-modified warriors to keep the Howlers at bay. Its nobles telepathically link themselves with psychic golden serpents, and are served by Gearsmen, clockwork automata animated by human souls. The kingdom was wracked by internal discord until the PCs from the second campaign mostly resolved the situation.

The Southern Desert: Wandered by pastoralist tribes who live in fear of a terrible devil of the wastes, the Black Jinn, who dwells in the House of Tarnished Brass somewhere deep in the desert. This desert was once the home of a cult revering a god whose name is both 'Fire' and 'Hunger' - the ruins of its sacred sites still dot the desert, haunted by firenewts and other servitors of this vanished faith. Ancient obsidian warriors roam its southern reaches. This whole region was menaced by the sinister schemes of the Red Architect until the PCs in the second campaign blew her up.

The Far Towns: Marshy region of isolationist farmers, recently brought back under the control of the City of Spires by the PCs from the second campaign. Threatened with annihilation by the Howlers until the PCs saved them with the aid of a giant robot snake and an order of ninja death cultists they founded by accident. Deep in the marshes live a matriarchy of hags, the remnants of the once-terrible dynasty of the Witch Queens, hiding from the world and served by loyal ogre clans who live in enormous halls woven from reeds. The PCs are currently working with them to find a way to neutralise the Howler threat.

Wastes of the Cannibal King: These once-fertile lands desertified as the weather control satellites of the Nameless Empire ceased to function - getting these back online has been a long-term goal of the PCs from the second campaign. In the Chaos Ages they were ruled by the fearsome Cannibal King, from whose tyranny the ancestors of the Tajarim fled long ago. Today they are dotted with haunted ruins, though the PCs have managed to clear out most of the worst ones.

The Howler Territories: Once a centre of sheep farming, this upland region was overrun by the Howlers - aggressive, territorial humanoids created by the dwindled Witch Queens, who hoped to use them as an army with which to reclaim their empire. The Howlers fled their makers and infested the hills and forests, driving out the human population and cutting off the roads between Aram and the City of Spires. The PCs from the second campaign have been trying to work out how to deal with them for years.

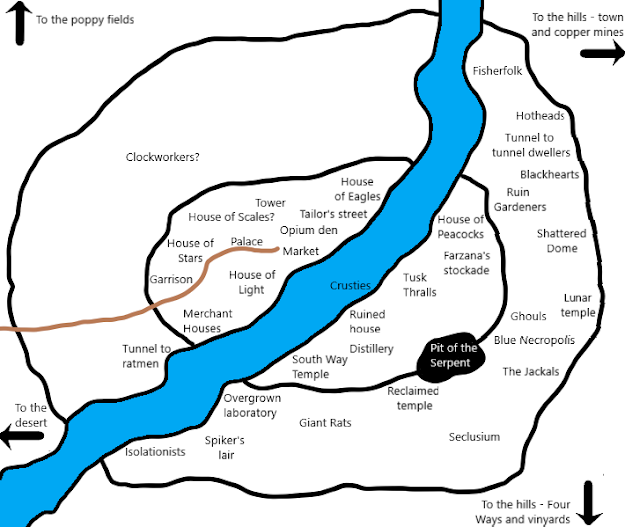

The Old Road and the City of Spires: Trade route that runs through the deserts north of the Pale Mountains, connecting Aram to the lands of the Tajarim and the kingdoms beyond. The major waystations along this road are the oasis-cities of Halwa, Wasat, and the City of Spires - this last is much the greatest of them, though it has fallen into accursed ruin since the closure of the road by the Howlers drove its merchant oligarchs to desperation and despair. In the days of the Nameless Empire the city was bombed flat, but immense underground complexes survived beneath the surface, and the treasures and horrors stashed within them have played a pivotal role in the city's history. The PCs in the second campaign seized power in a coup and now govern the City of Spires with the aid of a variety of freakish allies, including cyborg cultists, reformed diabolists, rat-man mechanics, and the remnants of the local nobility.

The Pale Mountains: These towering mountains are fought over by hardy human clans and furry abhumans with a fondness for gunpowder, which they manufacture from stinking nitre pools. One peak was hollowed out by the Nameless Empire as the resting place for its honoured dead, and a vault beneath it held the egg of the Great Worm, a larval hyperintelligence which presumably had something to do with the God-Mind project. It has since hatched, giving rise to a worm-cult which the PCs from the second campaign destroyed so that they could turn the whole mountain into a worm farm for their giant rat-breeding side-project.

The Lands Beyond: South of the Pale Mountains stretch lands that were once part of the Nameless Empire, but which were so devastated by bioweapon releases and orbital bombardments that civilisation here has never really recovered. One blasted city is inhabited by a nation of ghouls; other regions are home to wandering cattle-herding wagon tribes, or clans of hidden people who watch over the ruins of the doomed cities from which their ancestors once fled. Further south these lands are apparently ruled by lords who call themselves the Barons of Rust, but the PCs have never visited their territories.

.png)