Fourth and possibly last in this series, depending on whether I can muster the energy to do posts on any of Kabuki, Dawn, Aphrodite IX, or Fallen Angel. This one's just on gender, as Witchblade had little interest in race beyond the usual 1990s surfeit of honour-obsessed Yakuza assassins. Previous posts on Shi, Warrior Nun, and Ghost here, here, and here.

She's mostly forgotten now, but there was a time when Witchblade was a pretty big deal. Her comic ran for 185 issues, or 230-ish if you count the spin-offs and crossovers. It appeared monthly from 1995 all the way up to 2015: a run that dwarfs those of most of its competitors. Witchblade quickly became the tentpole of the 'Top Cow' comics universe, relegating older characters like CyberForce to the status of mere supporting cast. It had a manga series (2007-8) and an anime series (2006) and a two-season live action TV show (2001-2). And it provided a launchpad for Croatian artist Stjepan Šejić, who illustrated dozens of issues of Witchblade and its spin-offs between 2007 and 2013 before achieving online fame for his heartwarming lesbian BDSM romance comic, Sunstone (2014).

In later years, the creators of Witchblade were very open about the fact that they came up with her because Shi and Lady Death were the most successful characters in comics at the time, and they wanted a piece of the 'bad girl' action for themselves. However, unlike the other comics I've discussed in these posts, Witchblade was initially written by an actual woman, namely Christina Z, who wrote the first 39 issues. Its gender politics weren't as in-your-face as those of Ghost, but it was still pretty clearly about the difficulties of wielding female power in a world built on male violence and female victimhood.

Witchblade had two opening plot arcs. The first arc - issues 1-8 - tells the story of Kenneth Irons, billionaire, sorcerer, and all-around embodiment of patriarchal power. Irons is obsessed with the Witchblade, an ancient gauntlet which grants great power to its wielder... but all of its previous wielders have been women, and any man who tries to wear it ends up maimed or dead. When it merges with NYPD detective Sara Pezzini, Irons choreographs a series of events to try to compel her to yield it up to him, in a not-very-subtle allegory for the way in which powerful men manipulate women into giving up the power that is rightfully theirs. Sara resists and reclaims the Witchblade, and Irons apparently falls to his death.

The second arc - issues 9-14 - tells the story of Dannette Boucher, Irons's wife, who is basically a metaphor for the ways in which women become complicit in misogynistic power structures. Abjectly devoted to Irons, Dannette allowed him to experiment with implanting fragments of the Witchblade into her body, wilfully blind to the fact that he sees her sacrifices only as a means to enhance his own power. By the time he's done with her she's a monstrous mutant freak who constantly builds up power within herself, power that she can only get rid of by discharging it into other people, cooking them to death in the process. Realising that she's going to need a steady stream of victims, she demonstrates her internalised misogyny by setting up a modelling agency that keeps her supplied with desperate young women, whom she treats the same way Irons treated her: as disposable fodder. Sara hunts her down and reabsorbs her power into the Witchblade, killing her.

Both stories set Sara up as a kind of champion of her gender, against the cruel men who seek to steal the power of women and the abject women who help them do it. The Witchblade, as its name implies, is the symbol of her power as a woman. (Pop-feminist Wiccan neopaganism was everywhere in the mid-1990s.) It connects her to a lineage of female resistance stretching back through time, embodied by all the previous women who carried the Witchblade in other times and places - a fairly obvious metaphor for the project of feminist history, which at the time was very invested in excavating histories of 'inspiring' women who could act as heroines and role models for new generations of girls. Interestingly, similar 'lineage' scenes - in which heroines have visions of all the previous women who have wielded the same power they currently hold - appear in both Magdalena and Warrior Nun Areala. Buffy, with its conceit that the power of the Slayer has passed from one woman to another throughout history, represented a minor variation on the same theme.

So what qualifies Sara to wield the Witchblade, when most women and all men fail to do so? Simple: she's just stronger and braver and tougher than pretty much everyone else. She tells an anecdote at one point about how, when she was young, some boys encouraged her to climb a wall, and halfway up it she realised that they hadn't really done it because they wanted to see her climb: they'd just wanted to look up her skirt. She responds by climbing so far above them that their lustful leering is replaced by awe. But the limitations of this as a methodology of liberation are fairly obvious: it only works because Sara is stronger and braver than the boys who seek to humiliate her. That's great for her - but what about everyone else? What about all the girls who only possess average levels of strength and courage, the ones who will never be chosen by the Witchblade as its wielders?

Sara frequently expresses contempt for women too weak to walk her path, including her own mother and sister. She scolds Dannette for allowing herself to become a victim, declaring: 'Unlike you, I'm not stupid. I'm not going to blame my plight on some man who screwed me over. I refuse to let anyone, man or woman or object, decide my fate.' (Dannette, as she lies dying, replies brokenly: 'I'm sorry, Sara. I wish I could have been as strong, as independent, as you.') The comic is thus led towards a kind of 'Great Woman Theory of History': advancement comes through the actions of a series of heroines, women badass enough to take on the patriarchal weight of history and kick the shit out of it. Ann Bonney is named as a previous wielder of the Witchblade, and so is Joan of Arc. Everyone else just sort of cowers and waits for the next heroine to come along.

|

| Sara as phallic woman, from Witchblade #1. |

Even more than Ghost, Witchblade thus celebrates a version of femininity which wins power by being more masculine than the actual men. Sara Pezzini's only emotion is anger, her only mood is 'pissed off', and her only problem-solving technique is violence. Her favourite movie is Dirty Harry, she loves guns, she idolises her detective father, and when her partner is murdered she refuses to do anything as girly as talking to a counsellor: instead she works out her grief in true macho style, through boxing practise at the gym. However, whereas Ghost pairs its aggressive heroine with calmer, kinder men - 'beta heroes', as they were called in the romance literature of the time, before the internet poisoned the term beyond usefulness - Witchblade, like most female-authored media, pairs its alpha heroine with a man who is even more alpha than she is.

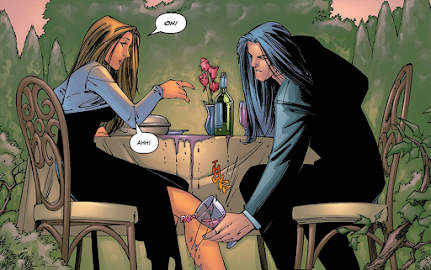

Enter Kenneth's personal enforcer, Ian Nottingham, a sexy bad boy so over the top that only a woman would ever have written him. He has knee-length black hair and a British accent and he catches bullets with his bare hands and cuts cars in half with katanas. Ian actually does wield the Witchblade for a while, despite his gender - probably because, like most male love interests written by women and unlike the ultra-macho Kenneth, Ian actually has quite a lot of femme traits, including physical and emotional vulnerability, a history of abuse at the hands of patriarchal authority figures, and a tendency to wear floor-length gowns and pose with pink roses. Ultimately, though, even a gender-fluid man isn't woman enough to handle the Witchblade, and it is to Sara that it always finally returns.

|

| Apparently Ian's pay is 'a high seven-figure salary and access to Irons's vast laser disc collection'. Adorkable. |

Witchblade is also notable for being much kinkier than its competitors. The whole 'bad girl' genre owed its existence to the fact that, in those innocent days, internet pornography had not yet become ubiquitous, meaning that there was still a market of horny adolescent boys willing to pay two or three dollars a month for comic books full of pictures of mostly-naked ladies. Witchblade provided fan service in spades: every time Sara activates the Witchblade it rips her clothes up, providing endless excuses for her partial nudity. (Later writers dialled this up to absurd extremes.) But it also repeatedly featured tableaux of men and women in bondage gear or fetish fashion, and depicted Ian and Kenneth's relationship as deeply homoerotic and sadomasochistic: in one scene Kenneth even dresses Ian up in chains and a rubber gimp suit for a spot of water torture. Sadomasochism, of course, also structures Kenneth's relationship with Dannette, Dannette's relationship with her victims, and even Kenneth's relationship with the Witchblade itself, which is explicitly described as an abusive relationship in which the more the Witchblade hurts him, the more he desires it. Even Sara's triumph over Kenneth has a sado-masochistic edge to it, as Kenneth pleads with her to show him the full power of the Witchblade by hurting him as badly as she can. Sara refuses, which reminds me of the old joke: Sacher-Masoch meets De Sade in hell. 'Torture me!' begs Sacher-Masoch. De Sade thinks for a moment and then says: 'No.'

|

| Ian Nottingham: assassin, anti-hero, gimp. |