Someone requested this at some point.

Skull and Shackles is a pirate-themed campaign, which, like most

Pathfinder APs, combines some good ideas and compelling imagery with heinous railroading, endless trash fights, filler dungeons, and miscellaneous bloat. I've tried to condense it down to something short and open enough to be useful. Previous 'Condensation in Action' posts can be found here:

Kingmaker

Rise of the Runelords

Curse of the Crimson Throne

Council of Thieves

Cults of the Sundered Kingdoms

Iron Gods

All

Pathfinder adventure paths are railroads, but this one is ridiculous. At one point the PCs have to persuade a bunch of pirates to make them Free Captains - but if they fail, then the pirate king appoints them anyway, because The Plot Must Go On. At another point they have to win a race against another pirate ship - but if they lose then the other ship is disqualified, so they win by default, because The Plot Must Go On. Sometimes the adventure just outright tells you not to let your PCs do things, as with this gem:

'Although Caulky knows where the Wormwood is berthed, you should discourage the PCs from visiting their former ship, as both Harrigan and the Wormwood have more roles to play, both later in this adventure and in the Adventure Path.'

'Discourage' them? How, exactly? By having rocks fall on them every time they approach the ship? By just informing them point-blank that they're not allowed to interact with the Wormwood until later in the adventure, because otherwise it might derail The Plot? 'You've all been press-ganged into serving on a pirate ship' is a great way to start a campaign, but from that point on everything is on rails. You

will lead a mutiny and take over your ship, you

will use that ship to become pirate captains, you

will take over an old fort to use as a base, you

will find and follow a treasure map, and so on. The idea that the PCs might want to do something else -

anything else - is given very short shrift indeed.

So, in line with the principles laid out

here, I've ditched all that, and just turned it into raw materials for a pirate-themed sandbox. Enjoy.

(NB: This map is not to scale: it's just intended to give a sense of the relative bearings of each location. The islands are much smaller than this, and the seas between them are much,

much bigger.)

Background: This hexcrawl describes a remote archipelago of lawless islands, long a haven to pirates, who sail out from its hidden harbours to prey upon shipping in the sea lanes beyond. The islands are rugged and heavily forested, and the surrounding seas are full of treacherous reefs, which has so far prevented the isles from being scoured clear of pirates by the fleets of the surrounding nations. The pirates often fight among themselves, but recognise the notional authority of their elected chief, the 'Hurricane King', and will rally behind him in the face of a real emergency. A nearby seafaring nation has become sick of all this piracy, and has sent spies and agents (see 0603 and 0605) to soften them up for a naval attack (see 1009).

The Hurricane King is appointed by a council of leading pirates, the Free Captains. In theory, once appointed, the decisions of the Hurricane King are final, with the Free Captains merely serving as his advisers. In practise, a Hurricane King who loses the support of the Free Captains is unlikely to reign much longer.

The current Hurricane King is

Kerdak Bonefist (see 0407). The current Free Captains are

Isabella Locke (0109),

Milksop Morton (0806),

The Master of the Gales (0708),

Avimar Sorrinash (0605),

Barracuda Aiger (0605),

Arronax Endymion (0605), and

Barnabas Harrigan (0603). Membership of the council is much more a matter of

de facto power than

de jure legitimacy, so any PC who owns their own ship and performs suitably piratical feats of daring-do is likely to be raised to the status of Free Captain sooner or later.

Hook: If this is the start of a new campaign, then you could have the PCs begin as unfortunates press-ganged into service aboard the

Wormwood (see 0505), who would then have to plot escape or mutiny. Alternatively, just begin with the PCs arriving at Port Peril (0605) looking for adventure. There's plenty of it about.

0102: Sinew-twined, scrimshawed skeletons are erected at intervals along the shoreline, here, as a warning to all who approach. In these flooded caves dwell a tribe of

grindylows, shark-toothed aquatic goblins who have a mass of writhing octopus tentacles instead of legs. The grindylows steal sailors from the decks of passing ships by night, dragging them down into their caves to drown and eat. Their caverns are full of masses of choking seaweed concealing lines of hidden, floating riphooks. Their queen spends most of her time doting on her blooded son,

the Whale, a gigantic grindylow who has never stopped growing, and is now much too large to leave the cavern which serves as his mother's throne room. She has accumulated considerable treasure over the years.

|

| A grindylow. |

0103: Amidst these rocks the lone survivor from the shipwreck at 0202 eked out many lonely years, before finally contracting ghoul fever from the mosquitoes. He hanged himself when he felt himself starting to transform, but this did not stop his corpse from animating as a

ghoul. Now he dangles, apparently dead and inanimate, from the roof of his ruined stockade, but his corpse will come to life and lash out savagely at anyone who comes within swinging distance. During his life he made many hunting expeditions against the ghouls who were once his shipmates, and his stockade is ringed with a circle of rotting ghoul heads on stakes - these are all filled with flies and mosquitoes infected with ghoul fever, which will burst out of them in stinging swarms if disturbed. He also managed to salvage most of the valuables from the shipwreck, which now lie buried beneath the dirt floor of his stockade.

0106: These seas are haunted by the ghost of

Whalebone Pilk, a cruel whaler who led his crew to their deaths at sea. Ships that pass through this region often glimpse a ghostly ship that emerges from the sea, sailing against the wind, or hear the tolling of a ship's bell. Those that linger too long are attacked by Pilk himself: his ship rises straight out of the water beside the unfortunate vessel, and

brine zombies come lurching aboard under the cover of darkness, seeking to grab the living, drag them onto their own vessel, strip them down for blubber, and behead them in front of their ship's bell. (The skulls of hundreds of previous victims litter the hold.) Pilk himself can suck the air from the lungs of his victims from several feet away. The ship's bell tolls continuously throughout these assaults: it is the locus of the haunting, and destroying it ends the curse and sends Pilk and his crew instantly back into the depths from which they came. Otherwise the curse will never end until the zombie crew have claimed their thousandth skull, at which point they will turn on Pilk, render his fat into oil, and sail their ship straight down to hell. Currently they're on six hundred and forty-three. Pilk is an infamous terror of the seas, and anyone who can prove that they have set him to rest will win great prestige with the pirates of Port Peril (0605).

0109: This island is surrounded by vast expanses of open sea, making it very difficult to locate without a map. Here, concealed in a secluded harbour, can often be found the

Thresher, the ship of

Isabella 'Inkskin' Locke, a pirate captain of some renown. Isabella suffered horribly at the hands of the ship's previous captain, a cruel man who knocked the teeth from her head and disfigured her body with crude tattoos. When the map to a legendary pirate treasure fell into his hands, he had a copy of it tattooed between her shoulders; but when he tried to follow the map, however, he ended up being killed by the sahuagin at 0209. Glad to be rid of her tormentor, Isabella entered into an alliance with the sahuagin king, and now acts as his eyes among the humans. She even had a new set of fanged false teeth made in imitation of theirs.

When it's not here at harbour, the

Thresher roams far and wide, serving the increasingly mad objectives of the sahuagin. (A band of them always swim alongside it in secret, and aid Isabella in her attacks on merchant ships and other targets.) In particular, it's only a matter of time before it participates in an attack on the fort at 0802. Her ship is also a regular visitor to Port Peril (0605). The chart tattooed between Isabella's shoulders is now the only surviving map that shows the location of this island, so defeating, tricking, or befriending her is likely to be the only way of locating it.

|

| Isabella Locke. |

0202: Years ago, a ship was wrecked here, carrying a pack of captive ghouls in a cage in the hold. The crash broke open the cage, and the ghouls proceeded to infect and kill all the surviving crewmen except one, who escaped into the uplands. (See 0103.) These

ghouls now live in a large, rotting tent in the swamps, painted with lurid faces, and creep forth at night in their tattered finery in search of prey. Half-eaten human body parts dangle from the surrounding trees. The local mosquitoes have also become carriers of ghoul fever, making this swamp an extremely dangerous place in which to spend any length of time.

0204: On this forlorn island stands a lone black tower, sacred to Dagon, demon lord of the seas. Years ago, it served as the stronghold of a terrible cult, until a coalition of pirate captains banded together to destroy them. The cultists retreated into the tower, the pirates pursued them, and no-one on either side ever came out. Everyone has avoided the place ever since.

The tower's ground floor is flooded, and infested with

flesh-eating eels. On the upper levels, ivory statues of drowned men vomit up rivers of cursed water to drown intruders, and roaming

beasts like great masses of animate intestines prowl mindlessly, searching for victims. Unintelligible whispers arise from holes in the black rock. The last survivor of the cult, now transformed into a

grotesque and bloated monster, lurks at the bottom of the tower, surrounded by the bones of her victims and treasures carved from coral and whalebone. The most valuable treasure of all here is a powerful magical sword,

Aiger's Kiss, which was wielded by one of the pirates who came to destroy the cultists, and still lies clutched in her bony hand today. Her son, 'Barracuda' Aiger (see 0506) would very much like it back, but has never been brave enough to come looking for it himself.

0207: Here, beneath the waves, lies the wreck of a legendary pirate ship, the

Brine Banshee. Famous for its speed, it outran every ship that tried to catch it, only to finally sink when an angry dragon turtle attacked it from below. There is nothing to mark its resting place, and PCs are extremely unlikely to find it without the Ring of the Iron Skull (see 0806) and the shinbone of its captain,

Vargus Brack (see 0708). They will also obviously need some way of travelling beneath the water.

Near the wreck lives an eccentric merman outcast named

Ormandar, who will come with his brood of pet

sharks to investigate any attempt to locate or disturb the shipwreck. If the PCs can ally with him, he could be persuaded to explore the wreck on their behalf, perhaps in exchange for sufficient quantities of fresh meat for himself and his sharks. If antagonised, he will unleash his pets on any divers.

The broken wreck itself lies on the seabed. Brack went down with his ship, and his skeleton, easily recognisable from its wooden leg, is still lashed to the wheel. There's not much treasure in the hold, but the ship's wheel itself bears a powerful enchantment, which greatly increases the speed and manoeuvrability of any ship to which it is attached. (This was the secret of the

Brine Banshee's success.)

0209: This island is extremely remote, and almost impossible to find without the aid of the map tattooed on Isabella Locke's back. (See 0109.) As well as giving the location of the island, the map also shows a skull with a golden tooth, and what might be either a rising or a setting sun. When seen from the south by the light of dawn, the rocky coast of this part of the island

does look a bit like a skull, and a heap of iron pyrite in a cave even gives it the look of having a gold tooth. This cave is where a legendary pirate once buried his treasure - but it's not there any more, because it was seized by a tribe of

sahuagin when they claimed these caverns as their lair. They also found an ancient stone throne, built ages before by the same cyclopses who built the city at 0501, which their chief,

Krell-Ort, claimed as his own. Unfortunately for them (and a lot of other people), the ancient magics of the throne warped his mind, filling him with messianic self-belief and dreams of conquest. Now his minions roam the archipelago, sinking ships and attacking settlements as the first stage in his (completely impractical) plan to claim all these islands as his own. In this he is aided by

Isabella Locke (see 0109), who scouts out potential targets for him, and sometimes even joins in his attacks.

The king's current objective is claiming the necklace in the fort at 0802 - the twin of the one he found in the buried treasure - which he has coveted ever since Isabella told him about it. He believes that if he can obtain it, it will be an omen that his conquests are fated to succeed.

The treasure that was buried in these caves, and subsequently claimed by the sahuagin, is legendary among the pirates of the archipelago, and finding it would bring great renown (and, of course, great wealth) to its discoverers.

0401: On this shore stands the crumbling ruins of an ancient castle, built on a superhuman scale by cyclopses in ages past. (See 0501.) It shows signs of recent renovation and even more recent destruction. A few years back a pirate mage named

Bikendi Otongu seized it for use as his base camp, from which he hoped to sally out and obtain the enchanted crystal at 0501, but he and his men had barely got the place fitted up when the cyclopses attacked and killed them all. Now their

ghosts haunt the fort, reenacting the events of their death each night. The one survivor was Bikendi's disappointing apprentice

Ederleigh Baines, who still cowers within the ruin, too scared of the cyclopses to leave. Being haunted by his dead master and comrades has driven him quite insane with trauma, fear, and guilt, and he is now a paranoid wreck, his hideaway ringed with improvised magical traps. If coaxed back into a semblance of reason he can describe the crystal that his dead master sought, and express the (correct) belief that Bikendi's ghost will never rest until it has the crystal. He will also mention that Bikendi discovered the location of some kind of sunken treasure nearby, but revealed it to no-one before his death.

If the crystal from 0501 is brought to the fort after dark and presented to Bikendi's ghost, he and his men will seize it and carry it away into the afterlife, ending the haunting. As payment, the departing ghost will flip over a loose paving stone, beneath which is hidden a detailed map showing the location of the sunken shrine at 0402.

|

| Bikendi's ghost. |

0402: This was once part of the same island as 0401, tipped into the sea by a great earthquake thousands of years in the past. When Bikendi Otongu (see 0401) came to the island he detected powerful magic beneath the water, and soon located a sunken temple beneath the waves, although the

giant shark that now inhabits it dissuaded him from investigating further. PCs might locate the temple either with Bikendi's map (see 0401), or just by randomly casting

Detect Magic spells, as it's only about 100' underwater. If the shark can somehow be killed or evaded, a small fortune in ancient gold and gems can be looted from the flooded ruins.

0407: On this rocky island stands the fortress of

Kerdak Bonefist, the Hurricane King. (The castle comes with the job.) Always paranoid about a potential coup, Kerdak paid a wizard to build a

cannon golem to protect him: an iron golem with cannons for arms, which is always on watch for attacking ships. His lieutenants are secretly

weresharks. The only person he truly trusts is

Powderkeg, his loyal powder monkey, who throws bombs with remarkable accuracy and will defend his master to the last.

0408: In this cave lies an enormous heap of bloody bones, resembling those of a slaughtered whale. In fact these are the bones of a dragon slain by a previous Hurricane King, and bound to obey whomever currently holds the title. If the bones are disturbed, or the castle attacked, then this

skeleton dragon will rise, wreathed in crackling electricity, to fight again. It cannot fly, but it

can swim, filling the water around it with electrical death.

0410: This island is the home of a miserable band of

shipwrecked mariners, survivors of attacks by the vampires at 0510. Corpses bob face-down in the water around the coast: these are actually

ghouls, who attack if anyone comes too close. The ghouls would have eaten all the survivors long ago were it not for the power of an enchanted spring up in the hills, which keeps the undead at bay. Unable to safely travel more than a mile from the spring, the survivors are desperate for rescue, and will light signal fires to alert any passing ships to their presence.

0501: Huge steps are carved into the side of these hills, ascending to the shattered ruins of a city built on a gigantic scale. Here, among the broken relics of their ancestors, live most of the remaining

cyclopses who inhabit this island, their attention now wholly devoted to the pressing problem of finding enough food to ward off famine. Their most sacred site is a mostly-intact temple, in which an ancient

undead cyclops still stands in eternal vigilance over an enchanted crystal of great value and power, the Immortal Dreamstone. The cyclopses will fight frantically to protect this crystal, but might be persuaded to exchange it for some kind of permanent solution to their food supply problems.

0502: Along the coast here stand huge one-eyed statues, carved from ancient stone. Their eye sockets are empty: once they held jewels, but these were all looted long ago, giving the isle its current name of The Island of Empty Eyes. An advanced race of

cyclopses once dwelt here, and the shattered remnants of their population still inhabit the island, though they have depleted its ecology so severely over the centuries that even the small number who remain are now on the brink of famine. They live by herding and butchering herbivorous

dinosaurs, and by sailing out in crude ships for fishing and whaling. They have ample experience of people arriving to try to pillage what little remains of their heritage, and view outsiders with intense mistrust.

0505: Here the good ship

Wormwood rides at anchor, looking for unfortunate souls to press-gang. Its thuggish master,

Mr Plugg, is a minion of the pirate lord Barnabas Harrigan (see 0603): his crew was depleted in a recent battle, and he needs more hands before he can resume his raiding. Among his recent victims is

Sandara Quinn, a self-appointed priestess of the sea goddess who maintains a ramshackle shrine on the harbourfront at Port Peril (see 0605): she's popular with the locals, who believe that her blessing brings them good luck at sea, and returning her would win the PCs a lot of goodwill. Plugg keeps order with the help of his 'pet', a simple-minded brute named

Owlbear Hartshorn, who is mostly kept imprisoned below decks. Hartshorn is a lumbering giant of a man, rendered brutal by years of mistreatment, but easily won over by any kind of kindness or sympathy.

|

| Sandara Quinn. |

0506: Here stands a temple of surprising size and grandeur, sacred to the goddess of the sea. The local pirates are a superstitious bunch, and the

priests aren't picky about where all these bloodstained doubloons are coming from, as long as the donations keep flowing in. Recently they ordered a particularly lavish golden idol, but it never arrived, much to their distress. (It was stolen by the wreckers at 1004.) They can provide a description of the route that the ship carrying it was supposed to take, and will offer both money and information in exchange for its return.

0510: This remote island is plagued by a feral band of

aquatic vampires, who waylay ships, turn their crews into

ghouls, break their masts, and drag them into a vast cavern as floating trophies. This cavern is now crammed with floating wrecks, and contains all kinds of long-lost ships and forgotten treasures.

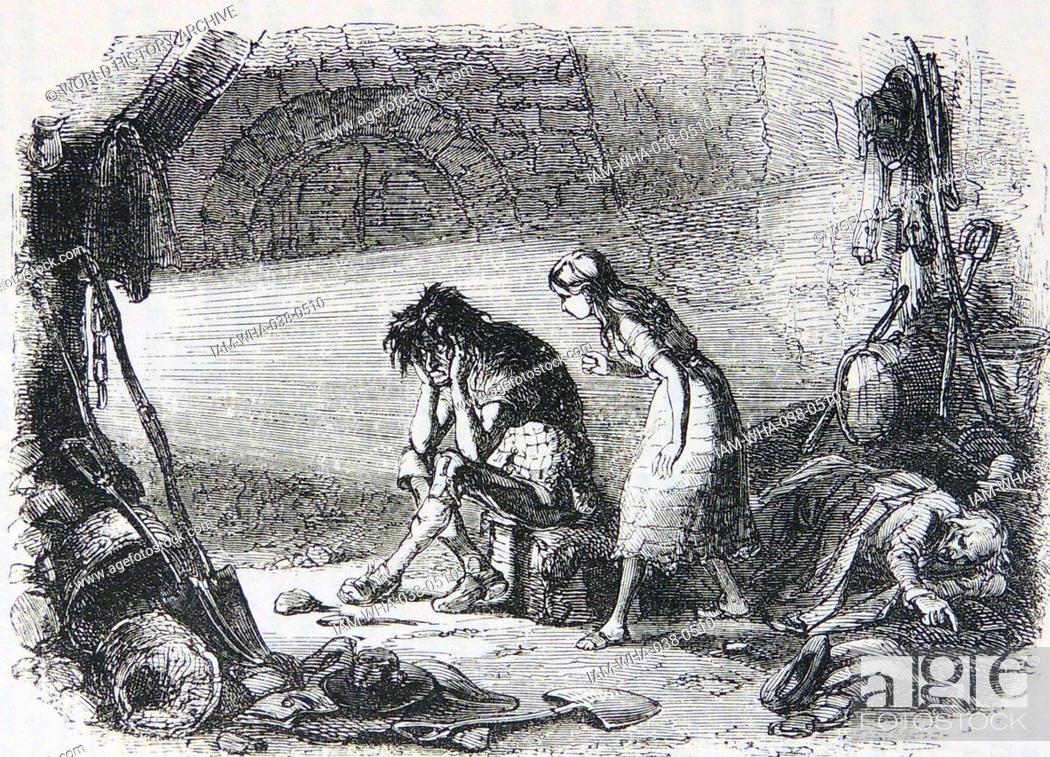

0603: On this island stands the fort of

Barnabas Harrigan, a pirate captain famous for his brutality. His island is guarded by a

trained sea serpent, and a band of

sea trolls serve him as shock troops provided he keeps them well fed. In the blood-stained dungeons of his fort a band of

masked cultists have taken up residence at his invitation: they revere a horrible god of pain, and keep their victims inside coffin-shaped cages, wound around with hooked chains. (Anyone liberated from this awful place will be desperately, pathetically loyal to their deliverers.) Harrigan chafes under the rule of the Hurricane King, and is secretly in league with Druvalia Thrune (see 1009): he has promised to help her conquer the isles by sending pilots to help her fleet steer through the reefs, and by murdering the Master of the Gales (see 0708) just before her attack, thus robbing the pirates of their two greatest advantages. In return, she has sworn to make him governor of the isles, and to permit him to rule them as he sees fit (i.e. horribly). Unless his treachery is detected before Druvalia makes her move, this plan will probably succeed.

|

| Barnabas Harrigan. Yarr. |

0605: Here, guarded by treacherous reefs and rocks, lies the pirate stronghold of Port Peril. Three Free Captains currently make this lawless town their home:

Avimar Sorrinash, 'Barracuda' Aiger, and

Arronax Endymion. Avimar is a werewolf, whose raids are notable for their savage ferocity. Arronax is a disgraced nobleman, hailing from the same nation as Druvalia Thrune (see 1009), who still maintains a pretence of aristocratic gentility despite the violence of his trade. Aiger is a successful pirate in his own right, but lives in the shadow of his legendary mother, who vanished in the assault on the black tower years ago. (See 0204.) He dresses in lavish and flamboyant fashions as though attempting to persuade everyone that he really is the kind of pirate lord he so desperately wants to be. He longs to reclaim his mother's legendary sword, but has never been brave enough to enter the black tower in search of it. If the PCs obtain it, he will try anything - bribes, threats, theft, violence - to get it from them.

All the Free Captains are frequent visitors to Port Peril, as is the Hurricane King himself. They and their crews are fiercely competitive, and are forever getting involved in brawls, gambling matches, drinking contests, and similar. (The exception is the Master of Gales from 0708, who holds himself soggily and morosely aloof.) The most serious escalation is for one captain to challenge another to a race around the island, as trying to navigate its rocks and reefs at speed can easily result in sinking ships and drowning men.

Port Peril is currently in a state of high alert, as word has reached the pirates that Druvalia Thrune and her fleet will be sailing to crush them any day now. As the port relies on its reefs for defence, there is much anxiety about the possibility of spies and traitors in their midst who might be willing to lead Druvalia's fleet to their doorstep. Given his nationality, Arronax Endymion and his crew are particular targets for mistrust - a mistrust that the

real traitor, Barnabas Harrigan, does everything he can to foster. (See 0603.)

Druvalia does indeed have a spy network in the town, which is organised by an alchemist named

Zarskia Galembar, who is tasked with informing Druvalia and Harrigan when the time is right to strike. The priests in 0506 have noticed Zarskia engaging in some pretty suspicious meetings on their temple grounds, but she's a major donor of theirs so they won't mention this unless the PCs have already earned their trust by, say, bringing them the idol at 1004. Jaymiss Keft (see 0708) also has his suspicions about her, as she's repeatedly come to Drenchport asking questions about the movements of the Master of the Gales, but he's so terrified of her that he will share this information only in exchange for something he truly values, like more of Vargus Brack's bones. (See 0207.) If cornered, Zarskia will gulp down a bottle of mutagen, hulk out, and try to rampage her way to freedom. PCs who can expose her and her spy network, probably incriminating Barnabas Harrigan in the process, will earn the gratitude of the Hurricane King.

0608: Amidst these miserable swamps stands a flooded crypt, the grave of four pirate captains who mutinied against the first Hurricane King. Their barnacled corpses will rise to attack anyone who intrudes within it. The locals give the place an extremely wide berth.

0708: On this soggy island stands the town of Drenchport, which is ruled by mysterious and ancient druid, the

Master of the Gales. (It's not clear whether the constant storms attracted him, or whether he's the one who brought all the storms, but either way it rains all the damn time.) His animal companion is a

giant squid, which prowls the waters around the island. The Master is a very hands-off ruler, who cares very little about what is done by the people of Drenchport provided they leave him alone. He is allied with the pirates of Port Peril (0605), because their presence ensures that these islands remain largely unsettled and beyond the reach of the law, which is just the way he prefers them. If Port Peril was seriously threatened he would summon winds and storms to throw its enemies into disarray.

Until about a decade ago, Drenchport was the home of a legendary one-legged pirate captain named

Vargus Brack, whose ship, the

Brine Banshee, was famous for its uncanny speed. Brack's exploits, and his mysterious disappearance several years ago, are still a frequent topic of conversation in the town. An eccentric scrimshaw artist called

Jaymiss Keft owns Brack's scrimshawed tibia bone, which he is extremely proud of. With the aid of the the Ring of the Iron Skull (see 0806), this bone could be used to discover the wreck of the

Brine Banshee at 0207.

0802: On this island stands a small fort, once the stronghold of a now-dead captain, and now maintained by his widow,

'Lady' Agasta Smythe. A small fishing village has grown up around it. Agasta wears a necklace of tinted platinum, gifted to her by her dead husband: it caught the eye of Isabella Locke (see 0109) on her last visit to the island, as it is the twin of another such necklace in Krell-Ort's treasure horde (see 0209). Krell-Ort is determined to obtain it, believing it to be a sacred treasure of the deep, and his

sahuagin agents are currently prowling around the island. Already they have been responsible for several dissapearences, which have thrown the locals into a state of panic, and it's only a matter of time before they and Isabella assault the fort in earnest.

0806: This island serves as the base of the infamous pirate captain

'Milksop' Morton and his ship, the

Screaming Satyr. The ship is so named because of its huge, outsized figurehead, carved in the shape of a screaming satyr holding a ballista-sized crossbow. Morton is a wizard, who has enchanted this figurehead to allow it to animate. When he attacks a ship, the figurehead comes to life, shoots a massive bolt with a chain attached into the side of the target vessel, and then reels it in with its massive wooden arms. Morton demands a toll from all he meets in exchange for allowing them to pass unmolested. He is an amoral opportunist, and is not above attacking his fellow pirates if he thinks he can get away with it.

Among Morton's possessions is the Ring of the Iron Skull, which bears a unique enchantment: anyone who holds part of a dead body while wearing it will always be aware of the location of the rest of the body. Morton uses it as a navigational aid: he has bones taken from cemeteries in various different ports, and uses the ring to ensure that he always knows where his ship is in relation to each of them. In combination with the shinbone of Vargus Brack (see 0708), the ring could be used to locate the wreck of the

Brine Banshee (see 0207).

1004: This island lies on the edge of the sea lanes, and is sometimes resorted to by ships seeking to refresh their stocks of food and water. It has recently become the lair of a gang of ruthless

wreckers led by a cruel illusionist, who uses illusion magic to conceal the treacherous rocks beyond the bay, causing ships to founder and their crews to drown in the surf. Among their recent victims was a ship carrying a golden idol to the temple at 0506, which would very much like to get it back.

1009: At this port the fleet of

Druvalia Thrune rides at anchor, ready to sail forth to subdue the pirates of the archipelago as soon as Zarskia gives the word. (See 0605.) Druvalia is an admiral from a kingdom that has long suffered from the depredations of the pirates: she has staked her reputation on crushing Port Peril, and has no intention of returning home empty-handed. However, she is aware that the rocks and reefs - not to mention the storms of the Master of the Gales (0708) - give the pirates a major advantage in defending their homes, and she thus hopes to take the islands by treachery, with the aid of Barnabas Harrigan (see 0603) and Zarskia Galembar. If these plans fall through, however, she will just attack Port Peril and hope for the best. Her fleet is greatly superior in size and strength to anything that the pirates can scrape together, but the rocks and reefs and winds are likely to be more than capable of evening the odds.

|

| Druvalia Thrune. |