First up, a brief announcement: the kickstarter for Knock! issue three has now gone live, packed with material from the old-school blogosphere's finest. It will also have a couple of my articles in it, so if you've ever wanted to own a physical copy of my d100 problem-solving items table but couldn't be bothered to print it out yourself then this is your chance.

Anyway. Something mildly interesting happened in my game this week: the PCs were negotiating with a king to end a civil war, which had started when the king had framed a mostly-innocent nobleman for his own misdeeds. The PCs wanted him pardoned, and suggested that the king should instead pin the blame on a different, more powerful nobleman, who was (a) actually much guiltier and (b) a drunken wastrel whom nobody liked. The king baulked at this, which somewhat confused some of the players. 'Isn't he a drunken incompetent?' one of them asked. 'Yes', I replied, 'but he's a very rich and influential drunken incompetent!'

The negotiations moved on and a compromise was ultimately reached, but thinking this over I feel there may have been a disconnect between the assumptions that I and (some of) my players were bringing to the table. To them, I think that getting rid of a corrupt lord who was despised by his own people seemed like pure upside, something that should be easily acceptable to everyone who wasn't him. Whereas my assumption, roleplaying as the king, was that openly moving against a powerful regional magnate - even one he personally disliked - would be something that he'd want to avoid unless he felt that there was absolutely no alternative. This isn't the first time I've felt such a disconnect: in reading discussions of fantasy RPGs and similar online, I've sometimes seen the view expressed that pre-modern aristocracies are purely parasitic, something that can be circumvented or done away with without disadvantaging anyone other than the aristocrats themselves. Frequently these seem to be rooted in modern liberal-democratic assumptions that aristocracies are obviously stupid ideas, and that any society that has one would be better off getting rid of it as soon as possible.

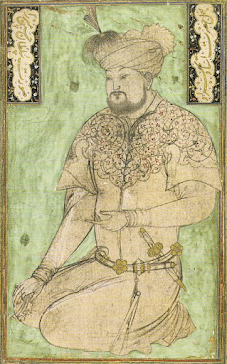

|

| Nice throne, but what exactly is the point of you? |

Now, I myself believe in democracy, and I am very glad that I don't have to spend my life bowing and scraping to the guy in the castle down the road. But I also think that social forms develop for a reason, and that if most of Europe and Asia kept circling back to social systems built around powerful land-owning aristocrats for thousands of years, then that probably wasn't just due to some kind of historical accident. When people think of aristocracies, I think they often tend to think of nineteenth-century aristocracies, lounging in their stately homes, expensive and decorative and mostly useless. But pre-modern aristocracies have a function, one that is not easily circumvented before the rise of the modern state, and understanding this function can help in making settings where all the obligatory dukes and barons and whatnot actually have some reason to exist.

Pre-modern life is local. There are no accurate maps, no accurate census data, no accurate statistics: the only way you can properly learn about a region is by living there, not just briefly but for years on end. Learning who lives where, what they produce, what they trade, understanding the social fabric that connects each family or community to those around it... all this requires specific local knowledge, and there are no shortcuts to acquiring it. Under these circumstances, establishing an effective system of resource extraction (taxation, conscription, etc) is often going to be the work of years, if not of generations. Any thug with an army can ride into a major population centre, steal everything not nailed down, and ride off. But if he wants his power to extend into the woods and the hills, the hamlets and villages, then that thug and his family need to be prepared to settle in for the seriously long haul.

This is the service that the local lord provides. If they've been there for long enough, he and his relatives will have wound their tendrils deep into all the prominent local families, bought off or intimidated all the local village 'big men', and learned through a grim process of trial and error roughly what kind of tax burden can be extracted from the region without actually triggering famine and/or revolt. He's probably been hunting and hawking in the area his whole life: he knows where to find all the hidden villages nestled deep in the forests, the ones that will never appear on any official map. His family's grip on the area will often have been decades if not centuries in the making. If you just banish them and install someone else then it might take a long, long time before his successors are able to exploit the region with anything like the same success.

|

| Thus I have made myself INDISPENSABLE! |

And above the local lord is the regional magnate, who is playing the same game one level up. As the local lords work their hooks into the local clans and prominent village families, so the magnate works his hooks into the local lords, gradually establishing a network of family ties and legal dependencies and bribes and threats and traditions and alliances that allow him to tap them for resources, and to call upon their aid in times of war. The whole system is intensely local and intensely personal: it's 'I know a guy who knows a guy' all the way down. A really well-entrenched regional magnate can run his domain like a petty king: the royal court can issue laws and proclamations, but the court is far away, and royal power can only extend out into the regions via networks of local intermediaries. In the little hilltop towns that the king has never heard of, the law is usually whatever the local lord says it is.

As a result, for a king to antagonise one of his regional magistrates is a really big deal. That magnate stands at the head of a patronage network that reaches all the way down into miserable, marginal settlements that only a few outsiders even know how to find, and alienating him - or alienating his family by executing or banishing him - risks disrupting the functioning of government across a whole chunk of the kingdom. Dispossessing his whole family and installing someone else could easily be even worse: while they'd presumably be loyal to you, it might take decades for their replacement to get a proper system of leverage up and running to replace the one you've just destroyed. (Remember, all of this is personal - a matter of 'you owe my brother a favour' or 'my cousin married your sister' or 'our grandfathers served together in the war' - and so none of it is straightforwardly transferable to a new candidate.) And of course there's always the risk that the offended magnate (or his family) will simply storm off and rebel, relying on their remote strongholds and local support networks to keep them safe. You'll probably win the resulting civil war - you're the king, after all - but winkling them out of their distant castles is probably going to be a slow and bloody business, and exactly the kind of thing that rival kings love to take advantage of if given half a chance.

So when the PCs in our session this week proposed to King Bahir that he should sacrifice Lord Maruf, I think that what they meant was 'You're the boss, so why don't you pin this whole mess on this under-performing middle manager?' But what I, in character as the king, heard was: 'Hey, that guy whose family network you rely upon to hold down the northern provinces and the border lords? The one whose people know how to extract tax revenue and conscript soldiers from the upland villages around the domains of the Broken One? He's expendable, right?' The fact that King Bahir personally disliked Lord Maruf was beside the point. He just couldn't afford to take that kind of hit unless he really had to.

Luckily, in the end the party circumvented the whole issue by staging an illusionary wizard battle in a desert instead!

People tend to think that 'medieval monarchies' were very absolute, 'the word of the king is law' and all that mess. The reality is, as you say, far more complicated and strange! Guilds are another thing that people tend to understand as some kind of company, but they have more in common with the Mafia than with a business company. In a sorta good way, I guess? Here in Valencia, in the 15th and 16th centuries, the guilds had the right to arm their members because of the perils of the barbary pirates... and, what a surprise, we had two very violent armed uprisings when the kingdom was changing. After the second rebellion, that right was revoked.

ReplyDeletePre-modernity social hierarchies and relations were a big mess! And I love to put them in my games (as an historian I simply can't resist) but I've experienced something similar to what you explain here.

Great post!

Hadn't heard that about Valencia. Interesting.

Delete'the word of the king is law' - yes, *of course*, Edward IV could converted the entire population of England to Zoroastrianism with one proclamation. Good grief, I doubt even Louis XIV could have managed that.

Nirkhuz - that's a great bit about the Valencian guilds. Would make for a great excuse for a PC party to do the whole 'wandering around armed to the teeth' routine that D&D PCs are famous for. 'No, we're not just roving murderers - we're agents of the *guild*!'

DeleteSolomon - the Louis XIV reference is significant, I think. I suspect that when people think of kings they often imagine early modern figures like Louis XIV or Henry VIII, absolutists presiding over cowed aristocracies, overlooking that (a) such setups are much harder in earlier periods, and (b) even once the relevant administrative technologies are in place, you still have to go through a long and brutal process of noble-cowing (fronde, etc) first!

'Cowed aristocracies' is probably the key here. A Breton peasant behaves in a very different fashion to a Versailles courtier, even if both are equally obedient.

Delete"Drunk and incompetent" is a lot better than "sober, competent, and ambitious."

ReplyDeleteIt's hard for one unmotivated and incompetent person to mess things up for the next rung of the ladder. They can make things difficult and tedious, but rarely in a catastrophic way. They add a predictable amount of friction.

In this case it was precisely the fact that the lord in question was the kind of inattentive administrator who would never think to wonder why he was being asked to raise a special levy of conscript soldiers - soldiers who never seemed to come back home - that made him useful to the king!

DeleteJust thinking about this. I have experienced similar situations before as well. I think it is very hard to communicate all the social intricacies to players in a short period of time. Comparing to dungeons, we have very precise and easily understood ways of describing parts of a dungeon, and we have a way of mapping them. The players don't have a clear way to picture that. It might be useful to very explicityly say to the players "this is how I am mapping the kingdom's relationships and these are the terms I use to describe people."

ReplyDeleteHaving the map would give the players something concrete to research and utilise and help them know they are on the same page as you.

You could use a relationship map or a heirarchy diagram for this. Maybe both? They both show different things.

The great thing about a heirarchy diagram is that you could roughly link the levels to character levels, the same is done with dungeons. This way, when a group of first level characters are talking to the king they would have a really clear idea about just how out of their depths they are and how quickly it could all go wrong for them.

In describing the situations, as a dungeon room you might say "You see a 10 foot by 10 foot room. There is a fountain in the middle. There is a door to the north."

For a ruler encounter you could say "You see the Duke of the Old Forest. His Vizier is standing to his left. There are currently border skirmishes with the barbarians to the north and something has crashed into the forest in the south-west."

A standard way of describing a ruler might be:

Title (including Rank)

Domain

Personal Worth

Personal retainers

Military

e.g. "You are talking to the Duke of the Old Forest, who rules the entire Old Forest including the towns Riverrun and Autumn Gold, he is worth about 8,000 gold. He has a household of about 15 retainers including Vizier Jafar the Demon Tamer and Mongo, Slayer of the Elves. He commands the Forest Watch of 100 foresters."

You could also not just give this information to the players. As long as they know the format they will know what the missing pieces are that they need to research. So they could ask around town first to understand the lay of the land. Or role-play it with other NPCs to find it out. "We need to know how much he is worth. Let's break into his estate to find out!" or "How strong is Mongo exactly? Let's challenge him to a duel."

I think there's something to be said for this semi-visual approach, and it's helpful to give players pictorial cues that aren't just conventional territory maps (which are bad at conveying hierarchical depth, and - particularly if they have polities delineated with neat borders and blocked-out shading - encourage people to see unitary states rather than dynastic networks as the key building blocks of society). If you want your relationship diagrams to make in-universe sense, you could always let players get hold of a family tree for the noble in question, which is a great starting guide to their personal affinity. I'd also encourage using ceremonial events, which you can map out like a dungeon encounter, as a great bit of visual shorthand for feudal relationships. Indeed, this is what pre-moderm aristocracies themselves did all the time; in the absence of bureaucratic documentation regulating everyone's relationships to one another, political systems had to constantly established and re-established by in-person ritual events like enfeoffments, entry processions, feasts, and religious festivals, in which the visual symbolism of each participant's actions spelt out their position in the system. Describing these ceremonies is a more memorable and interactive way of introducing setting details to players than infodumping reams of historical backstory on them. E.g. "the burgomaster of Brockentown is marching behind the duke's chariot with bared head and a noose round his neck, and behind him a float depicts a mounted horseman trampling a tower labelled 'rebellion'. Some of the watching crowd are dressed in ducal colours and cheering loudly, but others near the back are chanting 'restore our civic privileges!' Do you want to join in with either side?"

Delete@Jbeltman.

DeleteThat seems like a useful in game system. Yes it let's the players know who they are dealing with & how careful they may need to be. And I love how it gives gameable hooks by either presence or absence of info.

Might only add a couple of relationship cues like the OP suggests, one more line of info about his known alliances or resentments. "His eldest daughter married the Dukeling of Bavaria but is languishing in the High Tower after not producing an heir. He answered the Kings call when Bavaria was invaded by the Huns, but was late to the battle..."

I like the idea about events. The image of a person kneeling before a king to be knighted is such a powerful image of the medieval times, it would be great to capture something of that.

DeleteJbeltman, Montefeltro, Reason: Good points, all. I guess I'm always wary of submerging players in too much information and causing them to tune out: this goes double now that my gaming is all online. I tend to radically simplify family trees, for example, making every noble house improbably tiny, so as to avoid boring everyone to tears with lists of cousins and cadet branches.

DeleteI completely agree that clear and systematic data presentation is the way to go, though, and that even a simplified relationship/allegiance map is much better than none at all!

"Frequently these seem to be rooted in modern liberal-democratic assumptions..."

ReplyDeletePretty much. Any time my players run into someone who doesn't think like a well-fed, soft-handed urbanite with central heating: "these NPCs are so dumb. Why would anyone do [x]?"

In their own way, I think RPGs can be a great way of teaching answers to those questions. After struggling through several months of ruling over a pre-modern fantasy city-state in-game, one of my players confessed to being slightly disturbed by how much sympathy he now has for historical despots...

Delete(I should add that my players have, in fact, instituted a semi-representative oligarchy in the city they rule over, and are generally good and decent rulers unless you happen to be a worm cultist!)

DeleteMakes me think, D&D was created as a dungeoncrawl simulator, not a societal simulator, and we're stuck with it ever since. For the intended purpose sprinkle some keywords ("king", "knight", "peasant", etc.) on top for superficial Generic Medieval Fantasy theming, and you're good to go. Note that of the sources, the one work that was possibly the most grounded in actual history (even if only literary) - "Three Hearts and Three Lions" - gave rise to the most problematic character class. Not even cleric has to deal with baby-or-nun dilemmas, it's always the paladin, because only the paladin is ripped off a story where societal expectations matter.

ReplyDeleteOn players who unconsciously project their liberal democratic mindset onto in-game society: similar thing goes on with metaphysics. This is why the idea that gods need worship is so popular in fantasy - you just need to imagine a bunch of heavenly politicians squabbling for voter support.

I agree that the medievalism of most D&D settings is often paper thin, and that under the renfaire fancy dress they're mostly a weird mixture of liberal modernity and the Wild West. Whether this is worth the work of changing depends very much what kind of experience you want your games to provide. If you want Pendragon, it's kind of a big deal. If you want traditional dungeon fantasy, rather less so!

DeleteI am *so* tired of the 'gods need prayer badly' model of fantasy religion, which I find much less interesting than the conception of divinity in basically any real-world religion or spiritual practise. I love 'Small Gods' as much as anyone, but it's *thirty years old*, now. Let's all move on!

This is neat. I'd never really thought through what the role of minor nobility was. Like, nominally I knew they were a vital part of society, but if you'd asked me how my answer probably would have been pretty liberal-democracy-poisoned. :P

ReplyDeleteIt goes down to the village level as well. You can probably get your goons together and hang the village reeve but then you have to get a new guy who actually spends time with the peasants. In parts of Europe a local village demoracy develops.

DeleteLS: They were a vital part of the *state*, insofar as I don't think you could run anything resembling a medieval kingdom with a medieval level of social organisation without having something resembling a medieval aristocracy. Whether that made them a vital part of *society* as opposed to just agents of exploitation is a rather larger question!

DeleteI like this. I'd come to some similar conclusions trying to put semi-sensible feudalism in the background of one of my games. Players ended up thinking that sober, responsible local lords I'd intended to portray as basically reasonable rulers were "bad"... because they had reservations about letting a band of armed strangers do whatever they liked without a care for the effects on whether the iron traders came back next year or the harvest was interrupted... whereas an objectively worse lord was considered fine because he was too inattentive to care about travelling murderers deciding to "solve" local problems with murder so long as it didn't have an immediate effect on hunting, drinking or tax extraction.

ReplyDeleteIt did occur to me that an interesting but quite dark game could grow out of really emphasising this mismatch of interests, but it was a fairly light-toned game and the party wanted more wilderness so we left most of that stuff behind. I did manage to loop it back in eventually as a useful challenge - not only did they have to solve the knot of mundane and supernatural problems that all converged in one place, they also had to do it under the eye of a noble whose first reaction was oh no not you again.

In something more like a feudal pyramid I'm not sure I agree so much about the difficulty of substituting someone in the upper levels - but I think it's only practical with someone in a very close social circle. A wise king may never want to open the can of worms that is "which of the only three possible candidates could replace the wretched Duke of Backwater" unless the Duke openly rebels and loses.

I tried to email you, seems the address I have is out of date.

Now I'm worried I might have already told you that anecdote and then forgot. Apologies if I'm boring on. Too much work, not enough rpg.

DeleteNo, I've not heard the anecdote. The 'mismatch of incentives' point is a good one - the good lords *were* bad *from the perspective of the PCs*. Players *hate* authority figures trying to push them around - which is why they tend to gravitate towards lawless frontiers, just like their real-world equivalents did, and for the same reasons...

DeleteYou're still coming up as 'Unknown', but if you're who I think you are, you know my real name. Searching for that plus my university should give you my work email address!

Historically, mind you, vassal lords were often moved around from manor to manor. And from time to time (eg the Norman invasion) wholesale replacement of the barons happened too.

ReplyDeleteI'd have said the Norman invasion was one or two steps up from wholesale replacement of the barons... it's not far off proving Joe's point that swapping power structures in that sort of era/socioeconomic structure is hard, destructive and takes a generation or two to settle in. Perhaps it's a cost you might take as an invader who places a high value on the status of his sons, but a bad bet if you're an established ruler.

DeleteIn the ordinary, less-destructive level of change lords moved around a few at a time, and there was some of that going on all the time. But then again even with "and all that" going on, the post-Norman-Conquest era was built on top of some long-established societies and a fair bit of documentation. (isn't the Domesday Book an attempt to draw a line once and for all under the question "are there villages here we didn't know about"?). An earlier, sketchier stage of development seems to suit the oldschool RPG scenario even better.

OMG! It's DAVE MORRIS!

DeleteDave - permit me to gush a little. Blood Sword and Dragon Warriors *blew my mind* back in the early 90s, and I'm really not sure I've ever moved out of their shadow, imaginatively. Those books are seared on my brain at a level otherwise reserved for foundational childhood memories and unresolved personal traumas. Thanks *so much* for writing them.

You're quite right I've overstated the case, here, mostly as a reaction to seeing it so persistently understated elsewhere. History being what it was, the idea of a centuries-long bond between a noble family and their fief was often much more ideal than reality. But I think I'd agree with Unknown that reshuffling your lords still wasn't something you'd want to do lightly, especially in the earlier eras that D&D is (notionally) based on!

Aristocracy is a family business. You're not just kicking a baron off his plot, you are possibly kicking the people who will inherit it off as well, his cousin in the parish church and his brothers who administrate the dam system and the militia. The family business has internal feuds but they all want to keep it in the family.

ReplyDeleteFor the locals you are the weird outsider. For all they know, you could be the warlord with a band of thugs and no local sensibility. And that's how a lot of aristocratic lines start. In Britain there is a lot of local self-management where intermediaries like the village reeve and bailiffs smooth things out (and possibly take the ire of peasants, beating a bailiff is less serious than slapping the baron).

Aristocracy in the 19th century still keeps their traditions and beliefs that some things can only be learned during a lifetime. Aristocrats can find their way into careers in the national army or administration instead. You have a lot of disposable time to get good at things factory workers can't dedicate time to.

Good points all, Calvin. The importance of kinship networks and patronage networks (which often heavily overlap with one another) is another of those features of pre-modern life that was really important in reality, but which is hard to convey in RPGs without drowning your PCs in information about who married who's niece...

DeleteThat said, in my personal opinion at least, "you are all clients of the same Roman patrician" is as good a campaign starter as "you all meet in an inn".

DeleteThis sounds very similar to ideas from the book Seeing Like a State. The gist is that many societal structures we consider "natural" exist mostly for the purpose of making that highly local knowledge and those networks of influence legible to the central authority (i.e. the king) for the purpose of taxation and conscription. That includes things like the universal imposition of family names and the formalization of property rights.

ReplyDeleteMany DMs could learn a lot of this by playing a couple of hours of Crusader Kings II or III!

ReplyDeletePremodern administration was really messy and a lot less unified that people would think. There is a reason the Germanic invaders of the Roman Empire introduced feudalism: its a clear to understand system and easily scaled form the smallest village to the entire empire. Its also an easy way to satisfy minor chieftains by giving them land.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hands, the Romans themselves often relied on local self-rule combined that was kept loyal by the overwhelming force of the Legions and the dictatorial powers of the Proconsuls. However, as we know, this system was highly instable as it gave individual generals the means to challenge the central authority.

Early modern states went to great lengths to rationalize the state apparatus and marginalize the landholding aristocracy that wouldn't have been possible on the basis on an economy that was 90+% reliant on the income generated from agriculture. In Germany and Austria (and Switzerland?) there is still a seperate class of public servants (Beamte) that are hired for life and are almost impossible to fire, dating back to the 18th and 19th century when the state wanted to created an administration of professional beaurocrats that was independent on aristocratic client structure (at that time in the British Empire people were still expected to purchase military commissions).

Uff, typos.

DeleteI generally agree, except - it was stated from the beginning that blaming another lord HAVE started a civil war. So he was apparently more popular among his peers. And, of course, just finding a new scapegoat wouldn't finish the war, the king would need to make an adequate recompense...

ReplyDeleteMike