Most of this post consists of lengthy quotations from a novel published in 1841. You have been warned.

Anyway. Last month I read The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens. It's not a great novel. In fact it's barely a novel at all: more like a heap of random scenes, loosely strung together by improbable coincidences that serve to move the characters from place to place. The individual scenes and characters are often great, but I felt that the book as a whole was weaker than the sum of its parts. I was not surprised to learn that it was written in weekly installments.

It is, however, a work in which Dickens indulged his relish for the grotesque. Most of his novels are ostensibly set in the real world, while actually depicting something closer to the world of Gothic melodrama: but in this book the veil is particularly thin, and some of the characters who populate it barely even pretend to be human. Here, for example, is the novel's villain, Quilp:

The creature appeared quite horrible with his monstrous head and little body, as he rubbed his hands slowly round, and round, and round again—with something fantastic even in his manner of performing this slight action—and, dropping his shaggy brows and cocking his chin in the air, glanced upward with a stealthy look of exultation that an imp might have copied and appropriated to himself.

Mr Quilp now walked up to front of a looking-glass, and was standing there putting on his neckerchief, when Mrs Jiniwin happening to be behind him, could not resist the inclination she felt to shake her fist at her tyrant son-in-law. It was the gesture of an instant, but as she did so and accompanied the action with a menacing look, she met his eye in the glass, catching her in the very act. The same glance at the mirror conveyed to her the reflection of a horribly grotesque and distorted face with the tongue lolling out; and the next instant the dwarf, turning about with a perfectly bland and placid look, inquired in a tone of great affection.

‘How are you now, my dear old darling?’

Slight and ridiculous as the incident was, it made him appear such a little fiend, and withal such a keen and knowing one, that the old woman felt too much afraid of him to utter a single word, and suffered herself to be led with extraordinary politeness to the breakfast-table. Here he by no means diminished the impression he had just produced, for he ate hard eggs, shell and all, devoured gigantic prawns with the heads and tails on, chewed tobacco and water-cresses at the same time and with extraordinary greediness, drank boiling tea without winking, bit his fork and spoon till they bent again, and in short performed so many horrifying and uncommon acts that the women were nearly frightened out of their wits, and began to doubt if he were really a human creature.

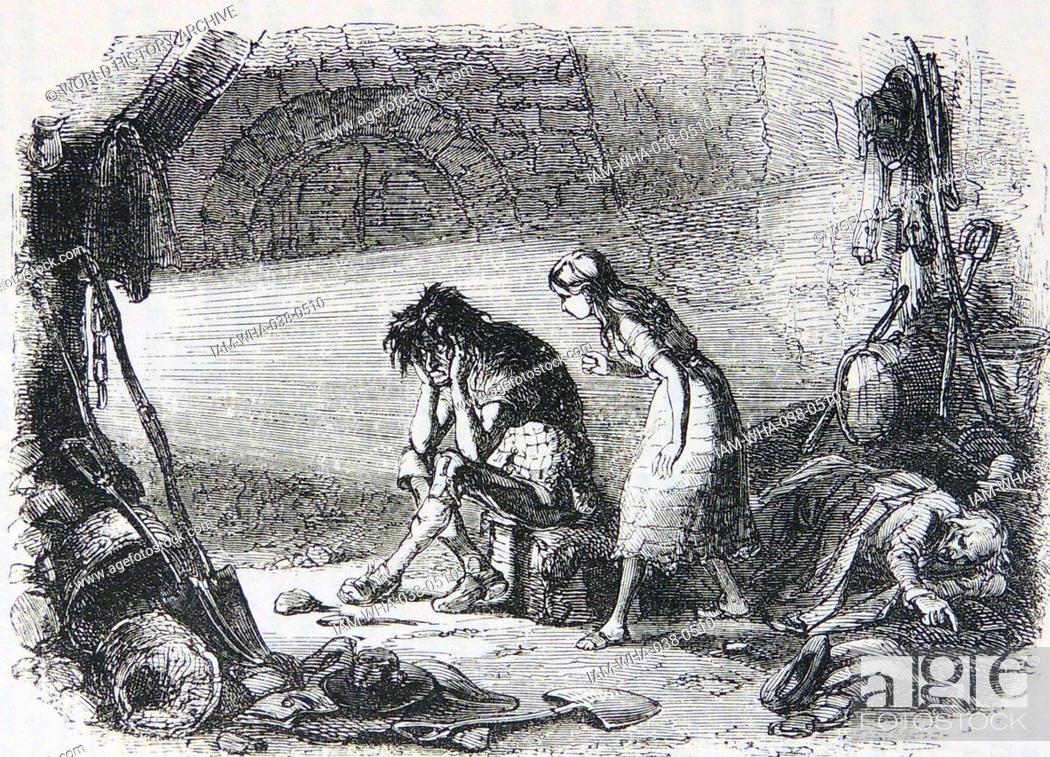

Yeah. An evil dwarf. He drinks boiling water. He never sleeps. His face seems to be able to act independently of its own reflection. He eats tobacco and water-cress for breakfast. He bends metal with his teeth. He presides over a horrible old wharf, where he is served by 'an amphibious boy in a canvas suit'. In the original illustrations he looked like this:

| Quilp is the figure on the far right. Attacking a giant wooden admiral. Like you do. |

Despite being notionally human, Quilp manages to be more goblin-like than most subsequent actual goblins. And this sort of thing keeps happening. Take, for example, this account of how people devolve into ghouls:

Again, notionally this is a 'realist' account of how Sampson and Sally decline into poverty; but in practise the language makes it clear that they've collapsed below the level of the human, becoming 'spirits', 'spectres', vile crawling things that live in vaults and cellars, creeping out on 'nights of cold and gloom' to slurp discarded offal out of gutters. A comparable process of dehumanisation, through which social conditions gradually transform people into something nonhuman, can be seen in the passage in which Nell encounters a laborer whose job it is to tend a factory furnace.

There were many such whispers as these in circulation; but the truth appears to be that, after the lapse of some five years (during which there is no direct evidence of her having been seen at all), two wretched people were more than once observed to crawl at dusk from the inmost recesses of St Giles’s, and to take their way along the streets, with shuffling steps and cowering shivering forms, looking into the roads and kennels as they went in search of refuse food or disregarded offal. These forms were never beheld but in those nights of cold and gloom, when the terrible spectres, who lie at all other times in the obscene hiding-places of London, in archways, dark vaults and cellars, venture to creep into the streets; the embodied spirits of Disease, and Vice, and Famine. It was whispered by those who should have known, that these were Sampson and his sister Sally; and to this day, it is said, they sometimes pass, on bad nights, in the same loathsome guise, close at the elbow of the shrinking passenger.

Again, notionally this is a 'realist' account of how Sampson and Sally decline into poverty; but in practise the language makes it clear that they've collapsed below the level of the human, becoming 'spirits', 'spectres', vile crawling things that live in vaults and cellars, creeping out on 'nights of cold and gloom' to slurp discarded offal out of gutters. A comparable process of dehumanisation, through which social conditions gradually transform people into something nonhuman, can be seen in the passage in which Nell encounters a laborer whose job it is to tend a factory furnace.

In a large and lofty building, supported by pillars of iron, with great black apertures in the upper walls, open to the external air; echoing to the roof with the beating of hammers and roar of furnaces, mingled with the hissing of red-hot metal plunged in water, and a hundred strange unearthly noises never heard elsewhere; in this gloomy place, moving like demons among the flame and smoke, dimly and fitfully seen, flushed and tormented by the burning fires, and wielding great weapons, a faulty blow from any one of which must have crushed some workman’s skull, a number of men laboured like giants. Others, reposing upon heaps of coals or ashes, with their faces turned to the black vault above, slept or rested from their toil. Others again, opening the white-hot furnace-doors, cast fuel on the flames, which came rushing and roaring forth to meet it, and licked it up like oil. Others drew forth, with clashing noise, upon the ground, great sheets of glowing steel, emitting an insupportable heat, and a dull deep light like that which reddens in the eyes of savage beasts.

‘I feared you were ill,’ she said. ‘The other men are all in motion, and you are so very quiet.'

‘They leave me to myself,’ he replied. ‘They know my humour. They laugh at me, but don’t harm me in it. See yonder there—that’s my friend.’

‘The fire?’ said the child.

‘It has been alive as long as I have,’ the man made answer. ‘We talk and think together all night long.’

The child glanced quickly at him in her surprise, but he had turned his eyes in their former direction, and was musing as before.

‘It’s like a book to me,’ he said—‘the only book I ever learned to read; and many an old story it tells me. It’s music, for I should know its voice among a thousand, and there are other voices in its roar. It has its pictures too. You don’t know how many strange faces and different scenes I trace in the red-hot coals. It’s my memory, that fire, and shows me all my life.’

The child, bending down to listen to his words, could not help remarking with what brightened eyes he continued to speak and muse.

‘Yes,’ he said, with a faint smile, ‘it was the same when I was quite a baby, and crawled about it, till I fell asleep. My father watched it then.’

‘Had you no mother?’ asked the child.

‘No, she was dead. Women work hard in these parts. She worked herself to death they told me, and, as they said so then, the fire has gone on saying the same thing ever since. I suppose it was true. I have always believed it.’

‘Were you brought up here, then?’ said the child.

‘Summer and winter,’ he replied. ‘Secretly at first, but when they found it out, they let him keep me here. So the fire nursed me—the same fire. It has never gone out.’

‘You are fond of it?’ said the child.

‘Of course I am. He died before it. I saw him fall down—just there, where those ashes are burning now—and wondered, I remember, why it didn’t help him.’

‘Have you been here ever since?’ asked the child.

‘Ever since I came to watch it; but there was a while between, and a very cold dreary while it was. It burned all the time though, and roared and leaped when I came back, as it used to do in our play days. You may guess, from looking at me, what kind of child I was, but for all the difference between us I was a child, and when I saw you in the street to-night, you put me in mind of myself, as I was after he died, and made me wish to bring you to the fire. I thought of those old times again, when I saw you sleeping by it. You should be sleeping now. Lie down again, poor child, lie down again!’

‘I feared you were ill,’ she said. ‘The other men are all in motion, and you are so very quiet.'

‘They leave me to myself,’ he replied. ‘They know my humour. They laugh at me, but don’t harm me in it. See yonder there—that’s my friend.’

‘The fire?’ said the child.

‘It has been alive as long as I have,’ the man made answer. ‘We talk and think together all night long.’

The child glanced quickly at him in her surprise, but he had turned his eyes in their former direction, and was musing as before.

‘It’s like a book to me,’ he said—‘the only book I ever learned to read; and many an old story it tells me. It’s music, for I should know its voice among a thousand, and there are other voices in its roar. It has its pictures too. You don’t know how many strange faces and different scenes I trace in the red-hot coals. It’s my memory, that fire, and shows me all my life.’

The child, bending down to listen to his words, could not help remarking with what brightened eyes he continued to speak and muse.

‘Yes,’ he said, with a faint smile, ‘it was the same when I was quite a baby, and crawled about it, till I fell asleep. My father watched it then.’

‘Had you no mother?’ asked the child.

‘No, she was dead. Women work hard in these parts. She worked herself to death they told me, and, as they said so then, the fire has gone on saying the same thing ever since. I suppose it was true. I have always believed it.’

‘Were you brought up here, then?’ said the child.

‘Summer and winter,’ he replied. ‘Secretly at first, but when they found it out, they let him keep me here. So the fire nursed me—the same fire. It has never gone out.’

‘You are fond of it?’ said the child.

‘Of course I am. He died before it. I saw him fall down—just there, where those ashes are burning now—and wondered, I remember, why it didn’t help him.’

‘Have you been here ever since?’ asked the child.

‘Ever since I came to watch it; but there was a while between, and a very cold dreary while it was. It burned all the time though, and roared and leaped when I came back, as it used to do in our play days. You may guess, from looking at me, what kind of child I was, but for all the difference between us I was a child, and when I saw you in the street to-night, you put me in mind of myself, as I was after he died, and made me wish to bring you to the fire. I thought of those old times again, when I saw you sleeping by it. You should be sleeping now. Lie down again, poor child, lie down again!’

Tellingly, this man isn't given a name. His life, family, and identity have all been sacrificed to a piece of industrial machinery, which he has come to regard as something more alive and sentient than he is. He himself is well on his way to becoming a mere spirit of the fire, his humanity entirely subsumed into the machinery around him. The only thing that would prevent this whole passage from appearing in a Warhammer 40,000 novel is that GW's writers could never sustain this level of prose.

Nell leaves the factory, and wanders on into a nightmare cityscape:

Advancing more and more into the shadow of this mournful place, its dark depressing influence stole upon their spirits, and filled them with a dismal gloom. On every side, and far as the eye could see into the heavy distance, tall chimneys, crowding on each other, and presenting that endless repetition of the same dull, ugly form, which is the horror of oppressive dreams, poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air. On mounds of ashes by the wayside, sheltered only by a few rough boards, or rotten pent-house roofs, strange engines spun and writhed like tortured creatures; clanking their iron chains, shrieking in their rapid whirl from time to time as though in torment unendurable, and making the ground tremble with their agonies. Dismantled houses here and there appeared, tottering to the earth, propped up by fragments of others that had fallen down, unroofed, windowless, blackened, desolate, but yet inhabited. Men, women, children, wan in their looks and ragged in attire, tended the engines, fed their tributary fire, begged upon the road, or scowled half-naked from the doorless houses. Then came more of the wrathful monsters, whose like they almost seemed to be in their wildness and their untamed air, screeching and turning round and round again; and still, before, behind, and to the right and left, was the same interminable perspective of brick towers, never ceasing in their black vomit, blasting all things living or inanimate, shutting out the face of day, and closing in on all these horrors with a dense dark cloud.

But night-time in this dreadful spot!—night, when the smoke was changed to fire; when every chimney spirited up its flame; and places, that had been dark vaults all day, now shone red-hot, with figures moving to and fro within their blazing jaws, and calling to one another with hoarse cries—night, when the noise of every strange machine was aggravated by the darkness; when the people near them looked wilder and more savage; when bands of unemployed labourers paraded the roads, or clustered by torch-light round their leaders, who told them, in stern language, of their wrongs, and urged them on to frightful cries and threats; when maddened men, armed with sword and firebrand, spurning the tears and prayers of women who would restrain them, rushed forth on errands of terror and destruction, to work no ruin half so surely as their own—night, when carts came rumbling by, filled with rude coffins (for contagious disease and death had been busy with the living crops); when orphans cried, and distracted women shrieked and followed in their wake—night, when some called for bread, and some for drink to drown their cares, and some with tears, and some with staggering feet, and some with bloodshot eyes, went brooding home—night, which, unlike the night that Heaven sends on earth, brought with it no peace, nor quiet, nor signs of blessed sleep—who shall tell the terrors of the night to the young wandering child!

You know that city, right? You've read about it in a hundred dystopian novels and OSR campaign settings. Some of you will have read about it on this very blog. (I called it the Wicked City.) But all that any of us have done is taken Dickens's metaphors a bit more literally than he does here.

Dickens had a gift for making 'normal' things seem weird and horrible. I've read a lot of horror fiction over the years, and few literary horror monsters manage to be as creepy as, say, the old man who buys David's coat in David Copperfield:

Into this shop, which was low and small, and which was darkened rather than lighted by a little window, overhung with clothes, and was descended into by some steps, I went with a palpitating heart; which was not relieved when an ugly old man, with the lower part of his face all covered with a stubbly grey beard, rushed out of a dirty den behind it, and seized me by the hair of my head. He was a dreadful old man to look at, in a filthy flannel waistcoat, and smelling terribly of rum. His bedstead, covered with a tumbled and ragged piece of patchwork, was in the den he had come from, where another little window showed a prospect of more stinging-nettles, and a lame donkey.

‘Oh, what do you want?’ grinned this old man, in a fierce, monotonous whine. ‘Oh, my eyes and limbs, what do you want? Oh, my lungs and liver, what do you want? Oh, goroo, goroo!’

I was so much dismayed by these words, and particularly by the repetition of the last unknown one, which was a kind of rattle in his throat, that I could make no answer; hereupon the old man, still holding me by the hair, repeated:

‘Oh, what do you want? Oh, my eyes and limbs, what do you want? Oh, my lungs and liver, what do you want? Oh, goroo!’—which he screwed out of himself, with an energy that made his eyes start in his head.

‘I wanted to know,’ I said, trembling, ‘if you would buy a jacket.’

‘Oh, let’s see the jacket!’ cried the old man. ‘Oh, my heart on fire, show the jacket to us! Oh, my eyes and limbs, bring the jacket out!’

I mean, fuck. I suspect that this guy was one of the inspirations for Tolkien's Gollum, but Gollum on his worst day was never as scary as Dickens manages to make the drunken old owner of a second-hand clothes shop.

| 1872 illustration of the Goroo Man, by Fred Barnard. |

What reading The Old Curiosity Shop brought home to me was just how little a sense of supernaturalism depends on the actual supernatural. I've written before about how easily the fantastical can cease to feel fantastic, especially in a game like D&D, but the converse is that even 'normal' things can swiftly take on a fantastical dimension if they're evoked in the right way. Dickens, who was always a massive ham at heart, even shows us some of the ways to do it. Give a character some sinister and distinctive appearance, mannerisms, speech patterns, and behaviour, and they can swiftly come to seem more genuinely monstrous than any out-of-the-book goblin, orc, or gnoll. An orc who jumps out a cave, tries to whack you with a sword, and dies after taking 1 HD worth of damage isn't really much of a monster: he's just an environmental hazard. But a creature that comes crawling from its cellar on lightless nights to suck the offal from the city gutters can still genuinely appall, even if it still has 'human' written on its character sheet.

With a bit of work, it might even be possible to make the village shopkeeper much creepier than the average D&D demon.

Oh, my heart on fire.

Oh, my eyes and liver.

Goroo...

|

| Illustration of Old Smallweed, by Mervyn Peake. |

Weren't most, or even all of Charles Dickens' novels published in weekly installments?

ReplyDeleteSome weekly and some monthly, I think. But I'd have to check.

DeleteLovely article. I've always recommended Dickens for GMs who wan to learn to describe things.

ReplyDeleteIt was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood, it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. It contained several large streets all very like one another, and many small streets still more like one another, inhabited by people equally like one another, who all went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next.

-Charles Dickens, Hard Times

He had a superb eye for detail. I also suspect that, like William Blake, he had the gift of perfect visualisation, so that the things he imagined appeared to him in exactly the same level of detail and vividness as things that were actually present. The precision and specificity of his descriptions is astonishing.

DeleteThe main problem is the length. His novels were written to be read aloud, but no modern D&D group is going to sit around while their GM reads them an entire paragraph of description. Like Bryce keeps saying, you get three sentences at most.

True, but you can sometimes break down the descriptions into phrases, usually paired descriptions. (You can do the same with Saki's early stories. I should do a post on how he wrote his witticisms).

DeleteIt's not red, it "would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it"

It's not smoke, it's "interminable serpents of smoke"

It's not a purple river it's "a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye"

The piston doesn't move up and down, it moves "like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness".

Etc.

The modern paragraph break has made me a lazy reader. Articles like this remind me that might not be a good thing.

ReplyDeleteDickens is one of those authors I always feel like I should read much more of, but never seem to get around to it. Really should do something about that...

ReplyDeleteThe length of the books doesn't help. They were meant to be read in installments: ploughing straight through one is like binge-watching an entire soap opera. Reading a few chapters a night is probably easier and more rewarding than, say, steeling yourself to read the whole of 'David Copperfield' in a week.

DeleteThat is some really evocative prose, to think I always thought of him as the Christmas Carol guy.

ReplyDeleteDickens was a key influence on Terry Pratchett.

ReplyDelete